My family and I pulled into the parking lot of a popular hiking trail in Acadia National Park this past summer, and I happened to make note of just how standoffish the rest of the people also pulling in appeared to be. And how standoffish I was to them. There was nothing remarkable about this until we actually got on the hiking trail.

We had gotten advice earlier in the day to hike the trail around the large lake counterclockwise, so as to head more downhill, and it so happened that many of the people from the parking lot went clockwise, meaning they ran into us head-on as we circled the lake. In the deep green woods of the trail overlooking a reflecting lake, we were greeted again and again by the same parking lot folks, this time with smiles and waves and simple recognition of one another’s existence. The difference of mannerisms in the two environments from the parking lot to the woods was startling.

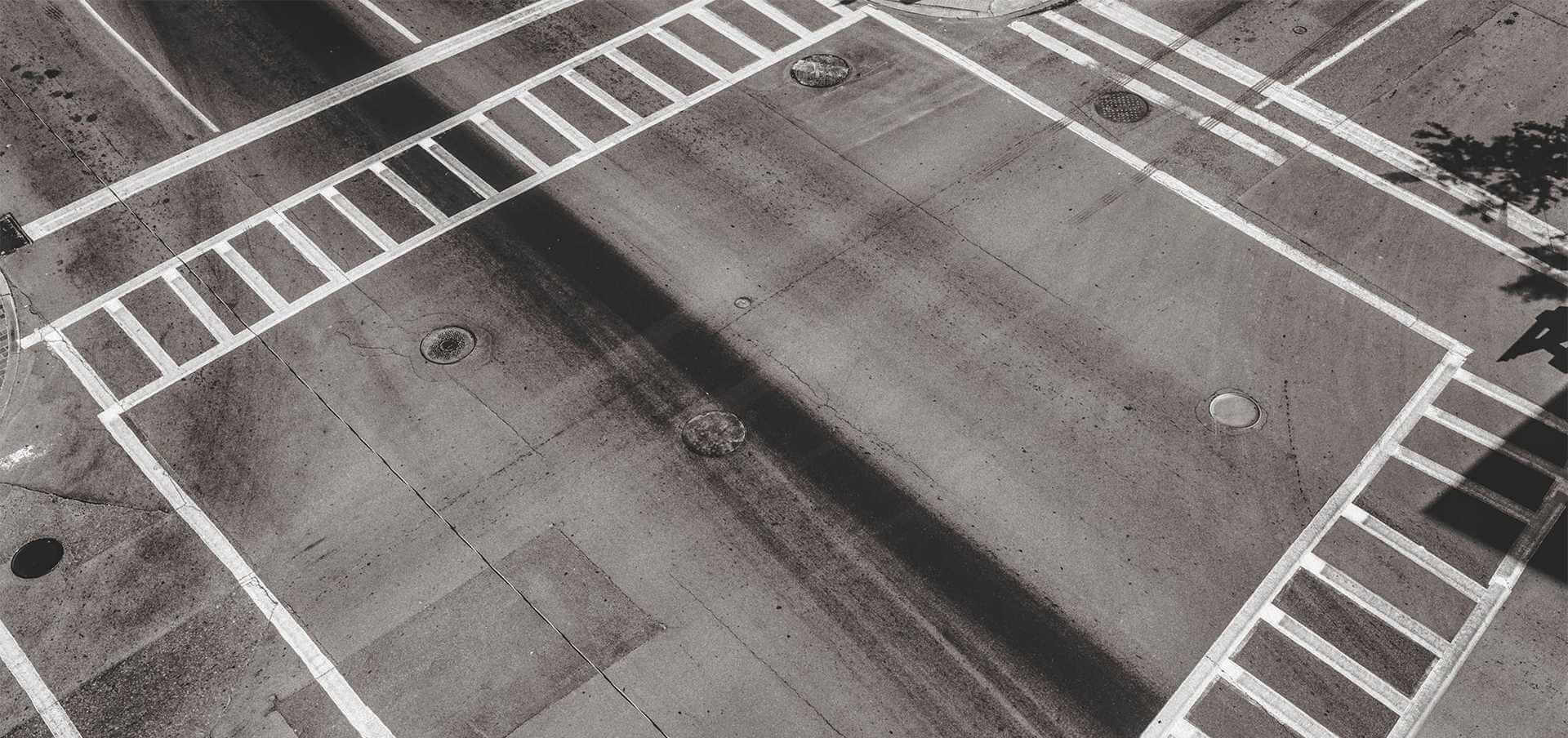

It got me thinking about intersections, the crossroads of life through which strangers’ paths come together briefly. How we intersect with people changes how we treat one another. Where we intersect also matters. What is the best way to come into an intersection? How do we make decisions together? How do we instill these values in our children? Or do we even instill these values or simply let our children loose into their own intersections?

This reminded me of earlier life musings on this same topic. In 2009 I started a small project I entitled An Intersection, A Handbook on How to Happily Cross the Street in which I tried to design the perfect traffic intersection for any possible situation. I decided to start as simply as I could with Goal One, “Create an intersection that allows individuals to cross paths in the most fair and efficient manner.” And then I would work my way up in steps to more challenging intersections, such as Goal Three,

Create an intersection where a large number people are all trying to cross the intersection at the same time and need to determine as quickly as possible the order in which each shall pass through the intersection that makes most sense (e.g. the ambulance with a bleeding victim gets priority over the “Sunday driver” out simply for leisure). What process do they use to determine this priority and how do they enforce it once it is established?

I wrote down my own answers and began asking friends and family members to come up with their own answers. Of course, in the end, I was left with more questions than answers and a muddled intersection worthy of Los Angeles traffic.

I began to invent a structure, a taxonomy of intersection conditions with a hierarchy of importance: pregnant woman in labor ranks higher than person who has to badly use the toilet, grumpy day at work commuter going home ranks higher than tourist out for entertainment, and so on...

My inspiration for this earlier intersection project had come from arbitrary sources, starting with sitting at a red light late at night with no one else around wondering why I wasn’t just driving through it. Then experiencing my first true roundabout (or traffic circle) in England and thinking I had the solution to my red light problem until I witnessed heavy traffic roundabouts, where red lights were installed or gridlock ensued (in a more circular fashion than my prior New York City experiences, perhaps “circlelock?”)

I began to notice how oddly wonderful it was when biking New York City streets that other bikers would stop at a light and make small talk with me. In contrast, we same New Yorkers go through painful efforts to not notice one another on the sidewalk and to squeeze our way past one another in bumper to bumper traffic in our four walled metal container vehicles.

I pursued this idea to such an extent that I contacted Transportation Alternatives, a local non-profit organization that looks to reclaim our streets for pedestrians walking and bikers and better public transit solutions. I told them I had ideas for developing a more efficient intersection (despite the fact that I had no idea what that intersection was going to look like...) They suggested I contact a firm that deals with urban planning in the city and propose my idea to them. And so I did. And surprisingly, they invited me into their office.

On the day I showed up for my appointment, I knew something was odd when I was brought into a conference room and asked if I needed a projector. As I waited, I realized they were expecting a presentation. A group of people walked into the room and sat down eagerly looking in my direction. I told them I did not have a presentation, just an idea. And I began talking about “democratic intersections,” places where people can converge and more equitably and efficiently get through any junction. “You’re suggesting people vote at an intersection?” one sceptic asked?

I swallowed heavily, “Er, yes?”

“How?” he retorted.

“By communicating with one another?” I barely was able to reply, as I sunk down further into my chair. Within a matter of minutes I was on my way out on a street with an angry conference room of people asking me to leave and to stop wasting their time. It was perhaps one of the dumbest moments of my life.

But the experience was also a good one for my research. They had an excellent point: imagine how inefficient our traffic system would be if at every traffic intersection we stopped and discussed the most fair and efficient way to pass one another? A horrible thought crept into my self-directed mind, what if– dare I suggest– the authoritarian traffic light intersection was the more fair and efficient process?

And this is where my rambling story of intersections finally collides on a path with Self-Directed Education. This thought about authoritarian decision-making and efficiency lead me back to my thoughts on running a democratic free school, specifically about the School Meetings. Anyone who has sat through a School Meeting can tell you, no five year old enjoys Robert’s Rules of Order (frankly, a lot of people who have not sat through a school meeting probably could tell you that as well!) Sometimes a decision just has to be made and the long process of democracy makes that impossible.

Other thoughts on democratic decision-making and the intersections of people’s lives began flooding in:

When I first started working at the tech startup Meetup, I remembered with disappointment asking the then CTO of Meetup, Greg Whalin, why the company no longer used a democratic process for deciding projects. Greg answered something along the lines of this: when a project goes through the conversation of a democratic process, the safest, most straightforward way always wins. And sometimes that’s just bad for business. Sometimes you need one person to take the risk of leading their idea though, to stick their own neck out. When applying that back to education, I thought, well, that leads us back to some administrator choosing a curriculum, and that’s exactly against my philosophy of education... but Greg’s words also rang true. How can it be that we need one person to pick a direction but democracy also allows for the most fair and efficient system?

I also thought of the time I sat on what I thought was a cobblestone sidewalk in Barcelona and began to paint a street scene, only to realize I was in a parking spot as a car bumper suddenly appeared in my face. This then lead me to realize the old Gothic Quarter of Barcelona has no distinguishing traits between street and sidewalk, bike lane and car lane and bus lane and fire lane.

It was around this time that my partner, Amanda Wilder, flew to Vietnam to make a film about the anniversary of the Paris Peace Accords. She became fascinated with the street scenes of Hanoi and shot footage of their street intersections. There were minimal shots of traffic lights there, no roundabouts, no democratic conversations. Instead, there was what at first looked like utter chaos— intersections jammed with people on mopeds carrying stacks and stacks of cargo, peacefully winding their way around one another. As I watched her edit the footage, watching the same scene over and over again, I realized something: they were all on mopeds. Like the closeness I had with bikers on New York City streets, there was a closeness of the Vietnam intersection. There was eye contact, the unspoken ability to quickly see body gestures, to understand velocity and direction.

There was no voting there and no authoritarian traffic light. And what looked like chaos was not chaos at all, but rather, a group of people autonomously negotiating their way through the intersection. It had structure, just self-determined structure— which, despite what the critics may say, is indeed structure. And there was a sense of mutual aid, people working together for the common cause of getting through. But this required a closeness and it required a form of body language, a connectedness that would not have been present had they been in cars, had there been traffic lights, or even had there been a system in place for each person to have equal time to voice their opinion with a democratic vote at the end. Like the same people in the Acadia National Park parking lot to the wooded trail, it was the environment that was different, not the people. And no taxonomy could be created to take into account the infinite variables necessary to produce a top-down hierarchical system that would rate the efficiency and needs of the members of that intersection at that moment.

And then I remembered an answer to Goal Two of my 2009 An Intersection project. The goal read, “Create an intersection that produces the highest amount of satisfaction for individuals passing through it possible. This intersection does not need to be fair or efficient at all, except of course, if efficiency and fairness are a part of the satisfaction.” My friend Dylan Whiting gave an answer that will stick with me for the rest of my life. He said that I had made an incorrect assumption about the intersection; the most satisfying intersection should not be passed through at all, but rather, it should elicit the feeling that one wishes to remain in the intersection forever.

And it is in this answer that I find my guide for my intersections with others, but most especially in my intersections with young people. How do I intersect with the young people in my life in a way that gives them the freedom to leave or to stay, to have command of their own voice enough to express which way they are turning so we all do not collide, efficiently enough that we do not get stuck on the rules and can simply pass using common language?

Sometimes the answer is a vote. Sometimes it is the authoritarian traffic light. Nearly all of the time it takes the time to listen to the other, to find closeness and familiarity, to contextualize one’s own needs in a manner that is not threatening but is always sincere. Sincerity is the key here, even when being jovial. It requires a true respect for the others, a respect for those indigenous to this intersection and to those who might be traveling through with a different purpose, different needs, different looks or ways of communicating or, dare I say, being of different ages.

It requires the willingness to sit down and create community with those there and then in that intersection, and that in turn requires mutual aid while at the same time paradoxically remaining autonomous. It requires living together at the intersection long enough to gain that respect for one another, to learn from one another. Maybe all it takes is a moment but it also might take a lifetime together. And no taxonomy or vote is going to enable that answer– it will only come from being there.

This is the ideal state of being together, in my opinion. And it is not taught but learned by being in such an environment. This is my definition of anarchistic education. One question remains: are the urban planners of the world ready for my next presentation?

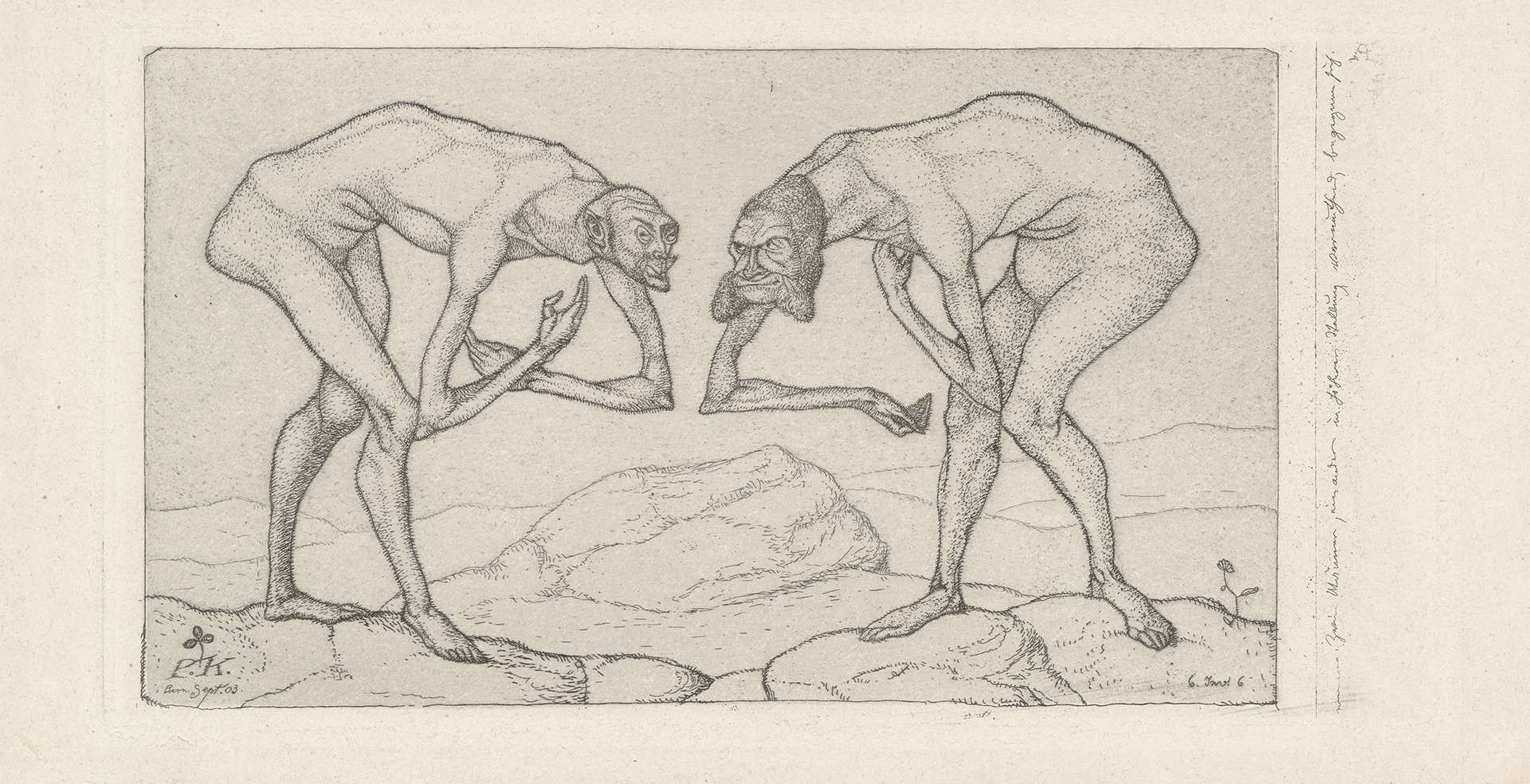

* Reproduction, including downloading of Paul Klee works is prohibited by copyright laws and international conventions without the express written permission of Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

If you enjoyed this article and feel called to give back to ASDE, here are ways you can support our work:

- Donate money

- Share our content with others! Click one of the buttons above to easily share on Twitter, Facebook, or email.

- Consider becoming a Contributor for Tipping Points

Tipping Points Magazine amplifies the diverse voices within the Self-Directed Education movement. The views expressed in our content belong solely to the author(s). The Alliance for Self-Directed Education disclaims responsibility for any interpretation or application of the information provided. Engage in dialogue by reaching out to the author(s) directly.