After my son Oliver (8) reported to me that he and his brother had found a rusty axe in the yard, I peered out to see my oldest child, James (10), happily commanding an old push lawn mower across the overgrown grass. The wooden handle of the mower was rotten, leaving little left for pushing with. The blades were so dull and rusty that his efforts only resulted in the grass being flattened, not cut. As I stood on the porch of the historic landmarked Goldman House peering out at the situation, the grandson of Sam Goldman, the homeowner, pointed out a path into the woods. He told me there is a forest of bamboo past there that his grandfather had planted, indicating that my children could play there as well, if they’d like. Seeing James grinning broadly at me, I went back inside to continue meeting with the Trustees of Friends of the Modern School.

Built in 1915, the Goldman House is one of the few remaining homes from the Ferrer Colony, part of the Stelton community within the township of Piscataway in central New Jersey, USA. The Colony was inspired by and named after Francisco Ferrer y Guardia, a Spanish anarchist who founded La Escuela Moderna (The Modern School) in Barcelona in 1901 1. La Escuela Moderna is the origin of a somewhat lesser known history of self-directed schools that predates many of the better known schools, such as A. S. Neill’s Summerhill (which opened twenty years after Ferrer’s first school).

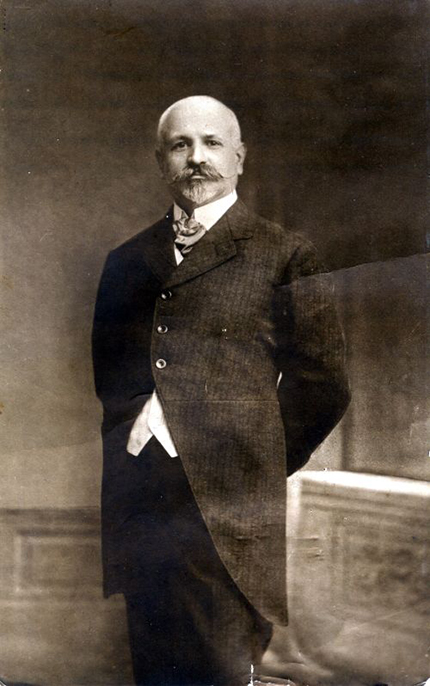

Although La Escuela Moderna itself remained open for only five years 1, a reported fifty-plus subsequent Modern Schools cropped up in and around Barcelona during Ferrer’s lifetime, and an approximate one hundred and twenty more used the radical textbooks that Ferrer had published 2. During a time when Spain was under command of the King and Catholic Church, Ferrer courageously argued for the secular co-education of boys and girls in an environment where rich and poor learn together, which was unheard of at the time. And so, he started “a school for children based on freedom of choice and expression, learning for learning’s sake and the imperative of finding one’s own truth” 3. In 1909 Ferrer was falsely accused of sedition by King Alfonso XIII for fomenting the Tragic Week in Barcelona and was executed by firing squad 3. Before his death, Ferrer wrote, “All the value of education rests in the respect for the physical, intellectual, and moral will of the child. Just as in science no demonstration is possible save by facts, just so there is no real education save that which is exempt from all dogmatism, which leaves to the child itself the direction of its effort, and confines itself to the seconding of its effort” 4.

Ferrer’s tragic death sparked an international movement of Modern or Ferrer Schools. The most significant and longest standing of which opened its doors on St. Mark’s Place in New York City in the Fall of 1911, along with an adult center entitled The Ferrer Association 5. Founded by the famous anarchists Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman 6, among others, it attracted students such as artist Man Ray 7, guest lecturers such as artists Robert Henri and George Bellows and writers and political activists such as Margaret Sanger, Jack London, and Upton Sinclair 8.

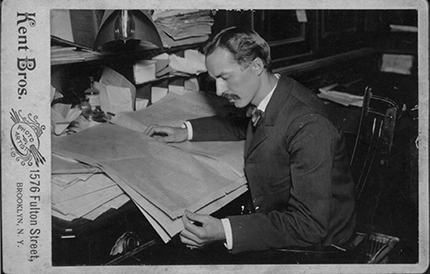

In its early years the New York Modern School had multiple principals, including the writer, historian, and philosopher Will Durant 9. The school also relocated a number of times, first to 12th Street and then uptown to 107th Street (exactly one block north of the self-directed Agile Learning Center, where my two school-aged children now attend). On July 4th, 1914, anarchists associated with the Ferrer Association, the aforementioned adult center situated within the school, failed in their plan to assassinate business magnate John D. Rockefeller with a homemade bomb. They instead blew themselves up in their Lexington Avenue apartment, just south of the school between 103rd and 104th Streets 10, 11. Fearing they would be considered accomplices of the attempted bombing, the school community decided to move out of New York City at the start of 1915. The community decided to open a colony and soon purchased sixty-eight acres of land in New Jersey 12. Thus the Stelton Modern School and Ferrer Colony were born.

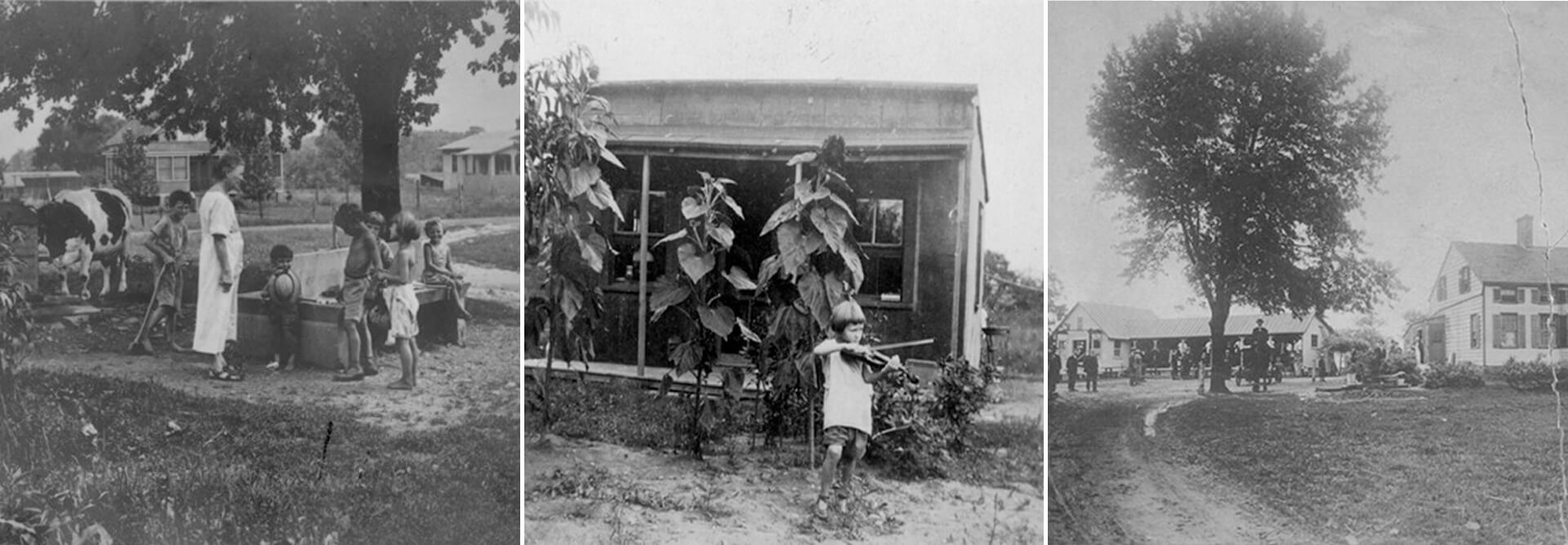

In its early years Stelton had over eighty students, roughly half of whom lived in the school’s boarding house, the other half living in homes with their parents on the colony’s property. When they first opened, the boarding house children slept on straw mattresses and neither the boarding house nor the homes had indoor toilets, plumbing, or heating 13. At its new location the school still continued to have difficulty keeping a steady principal over the years. The most notable and longstanding principals were two husband and wife teams, Jim and Nellie Dick and Elizabeth and Alexis Ferm (the latter of which interestingly enough opened the first recorded self-directed school in New York in 1901, the same year Ferrer opened his school in Barcelona) 14.

When the Ferms, nicknamed Aunty and Uncle, arrived at Stelton in 1920 the school curriculum had been “‘largely academic.’ But Aunty and Uncle ‘reshaped it entirely.'” The Ferms restructured the school so that arts and crafts and play were central to the core of the children’s activities. Activities such as nature hikes, “printing, weaving, carpentry, basket-making, pottery, leather crafts, metal work, not to mention singing, dancing, and sports became ‘the primary activities for teachers and pupils'” 15.

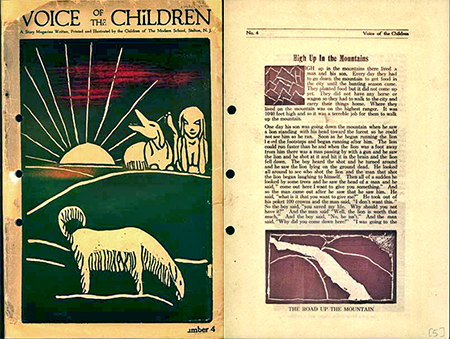

Other notable staff joined the school and contributed to its uniqueness. In 1922, Paul Scott, “a former agitator and tramp,” 16 began Voice of the Children, a magazine that was hand printed and typeset by students at Stelton. Joseph Ishill later took over the publication, which remained in print until 1941 17. It was said of Ishill that, “none made a deeper impression on the colonists or played a more important role in the anarchist movement” 18. In 1926 John Scott filled in for the Ferms for a period and started “a youth movement in which teenagers and young adults might learn to make a living from the soil” 19.

Over the years, the Dicks and the Ferms replaced one another several times as co-principals of the Stelton School. The Dicks left Stelton to found their own school in Lakewood, NJ, prompting the last of these exchanges, which occurred in 1933 when the Ferms stepped in for the Dicks a final time. The school began to decline over a period of time with the Great Depression, conflicts related to the Spanish Civil War, and the rise of Stalin. With the start of World War II, the military base Camp Kilmer moved in next to the colony, marking a turning point at which the colony no longer fit into its utopian setting. In 1944 Aunty Ferm died and left Uncle Ferm to carry on the school until 1953, when the school finally closed its doors 20.

Other Modern Schools, sparked by Ferrer’s death, ran for brief periods of time. The Modern Sunday School opened in Philadelphia in October 1910 and a Francisco Ferrer Club opened in Chicago that same year. A day school opened in Portland, Oregon at the same time as the New York school in 1911. There were Ferrer schools and centers in Salt Lake City, Seattle, Brooklyn, Detroit, Lakewood and Paterson, New Jersey, and Indiana, as well as many more abroad. Mohegan was another notable colony, also in the New York metropolitan area. However, none of the other schools, centers or colonies ever lasted as long as the Stelton school. As one historian put it, “the most important Ferrer school in the United States was started in New York City. Enduring more than four decades... it was the longest-lived experiment of its kind anywhere in the world” 21.

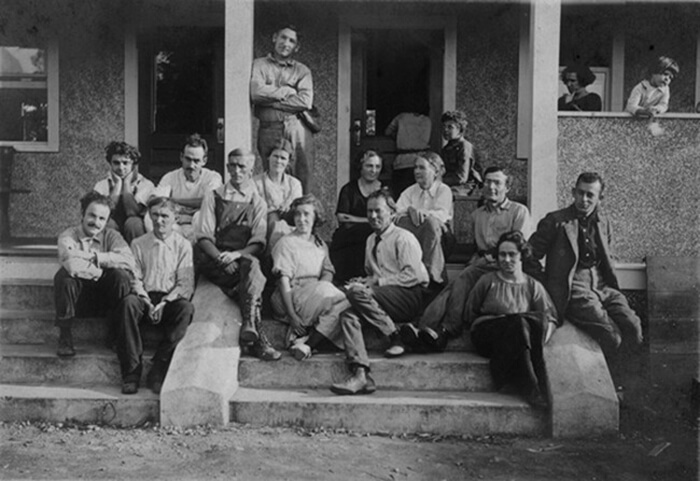

In 1973, Friends of the Modern School (FMS) was formed after increased research interest on the history of the Modern Schools, most notably Paul Avrich (from whom most of the above research comes) and Lawrence Veysey. FMS has consisted primarily of former students of the Stelton Modern School as well as the children of some of those original colonists and some historians and researchers.They held reunions at the New Brunswick Scientific Co., whose CEO, David Freedman, was a Modern School student in the 1920s 22.

Fast forward some time to 2007, when I opened the Teddy McArdle Free School, a democratic free school inspired by my readings on the Summerhill School in Leiston, England. At the time I had not heard of the Modern Schools. In the early fall of that year, Jon Thoreau Scott, a student at Stelton and the son of John Scott, the Stelton School teacher previously mentioned, walked into my school and introduced himself. Unbeknownst to me, I had possibly opened the first self-directed school in New Jersey since the closing of Stelton some sixty or so years earlier. Overwhelmed with the responsibilities of running this school mostly by myself, I vaguely remember having been honored that Scott visited and wanting to hear about the history, but I took it no further at the time.

Nearly ten years later, I found myself defending the right to continue to send my children to a self-directed school in an educational custody battle with their mother. Preparing my defense of this method of education made me more and more interested in the history of self-directed education, and my research dated the method as far back as 1805, when the Swiss educational reformer Johann Pestalozzi opened the institute at Yverdon. That is a more than two-hundred year history, which predates conventional education as we now know it by roughly a century. In my studies I unearthed the rich history of the Modern Schools again and remembered that brief visit from Jon Thoreau Scott. All of a sudden, I regretted having not given more significance to his visit ten years prior.

As I continued to research Stelton’s history, and being a Rutgers University alumnus who lived on its campus in Piscataway, New Jersey, I became fascinated with the fact that Stelton existed in the same town where I had spent some of my own education. When I finally found the address of the Goldman House in the magazine Weird NJ, I mapped it, only to realize that it was literally blocks from where I lived as an undergraduate. I then discovered that the Rutgers University Alexander Library, “about three miles from the location of the Stelton Modern School and Ferrer Colony, now contains the largest collection of archival materials about the Modern Schools” 23.

I soon reconnected with Jon Thoreau Scott and then met Fernanda Perrone, a Special Collections Archivist at Rutgers University, who put together the Modern School collection. I asked about Friends of the Modern School reunions, only to find out that for the first time in forty-three years, there wasn’t one. And so, with no other actions I could take, I began making weekend trips to the Alexander Library to sift through the archives. By looking through the photographs, letters, and notebooks, the people in these accounts started to become alive to me. They seemed largely no different than I am now, struggling to make sense of how best to learn, how to adhere to one’s beliefs despite the odds, how to survive.

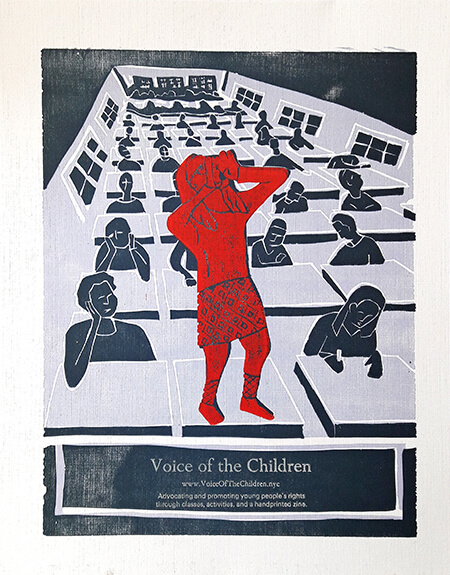

When I came across original copies of the hand-printed magazine, Voice of the Children, in the archives, something suddenly occurred to me. It was a realization that this is exactly what I needed to do: to make these same hand-printed magazines with children. Literally the next day I signed myself up for a letterpress printing course at the Center for Books Arts on 27th Street in Manhattan. Soon after learning the techniques, I began working with children on lino printing in the three different self-directed schools where I am teaching or volunteering in New York and New Jersey. Then I ordered a small printing press from England, from the only company in the world that refurbishes these small, old presses. Thus I began printing type with children as well, almost exactly as the original creators of Voice of the Children had done ninety-five years ago.

I then contacted Fernanda Perrone and Jon Thoreau Scott and asked Friends of the Modern School for permission to use the name Voice of the Children for the hand-printed magazine I intended to start. They spoke to the Trustees, who gladly agreed. So I incorporated and purchased the web domain http://VoiceOfTheChildren.nyc to start offering classes and activities. I am in the midst of printing our first magazine, entirely created by handmade lino prints and type set by children. My hope is to have the classes and the magazine ready for the fall 2017 school year.

Later, I found out that Jon Thoreau Scott was organizing a 2017 Friends of the Modern School meeting, and I was invited. The meeting was to be held at the Goldman House in late May. Leaving my partner Amanda and our six day old daughter Oomi at home, I hopped on a New Jersey Transit train in Penn Station with my two older children, James and Oliver, headed for New Brunswick. I brought with me copies of the Voice of the Children posters I had hand-printed in my letterpress class in order to distribute them at the meeting.

A historian who was writing an article on the Modern Schools picked us up in New Brunswick and drove us the few miles out to the house. The grass on the front lawn was waist high, the house slanted slightly in places. Most of the Friends were already in the driveway, along with a friendly cat, when we pulled up. I shook hands with Jon and Fernanda and was introduced to others. Among them was Rose, who corrected her introducer as she was not yet one hundred years old, not until November of this year at least. In the house Leo G., Bill Giacalone, and Jon Thoreau Scott confirmed that they were students at Stelton and remember running off “throwaways” and other announcements on a large tabletop printing press, the same press that Voice of the Children was printed on.

A new Vice President for the Board of Trustees was needed. When I volunteered, everyone agreed. They said they need more young people to become interested. When I said there must be more people interested in this history, and I just might know where to find them, Styra Avins, the woman sitting beside me who was the daughter of a music teacher at Stelton and attended the school for a year with her twin sister in the early 1940s remarked, “The more distant the history of the Modern School becomes, the more romantic it will be to young people.” Like the Man of La Mancha chasing windmills, this chivalrous history could not be more romantic to me. Surely someone else out there agrees with me?

I wonder if, reflecting on their own childhood many years from now, my own children will recollect an old push mower on a lawn of some house their father took them to that had something to do with anarchists and colonies. And I wonder who will be listening to their continuation of this story.

The Friends of the Modern School Annual Meeting will be held on Friday October 27, 2017 from 2:00 to 5:00 PM at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, NJ, USA. For more information, please go here or contact Alexander Khost at alex@voiceofthechildren.nyc.

[1] Avrich, Paul, The Modern School Movement: Anarchism and Education in the United States (1980), page 20

[2] Avrich, The Modern School Movement, page 26

[3] Avrich, The Modern School Movement, page 32

[4] Mercogliano, Chris, “Paul Avrich’s The Modern School Movement,” http://www.spinninglobe.net/spinninglobe_html/avrich.htm

[5] Ferrer, Francisco, Mother Earth, December, 1909 issue.

[6] Avrich, The Modern School Movement, page 69

[7] http://www.theartstory.org/artist-ray-man.htm

[8] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Modern_School_(United_States)

[9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Will_Durant#Teaching_career

[10] https://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2013/01/the-strange-story-of-new-yorks-anarchist-school/266224/

[11] Avrich, The Modern School Movement, page 183

[12] Avrich, The Modern School Movement, page 214

[13] Avrich,The Modern School Movement, page 237

[14] Avrich, Paul, Anarchist Voices: An Oral History of Anarchism in America (2005), page 194

[15] Avrich, The Modern School Movement, page 275

[16] Avrich, The Modern School Movement, page 278

[17] Avrich, The Modern School Movement, page 233

[18] Avrich, The Modern School Movement, page 231

[19] Avrich, The Modern School Movement, page 302

[20] Avrich, The Modern School Movement, pages 320-321

[21] Avrich, The Modern School Movement, page 57-68

[22] from an email conversation I had with Jon Thoreau Scott

[23] http://friendsofthemodernschool.org/friends-of-the-modern-school/

If you enjoyed this article and feel called to give back to ASDE, here are ways you can support our work:

- Donate money

- Share our content with others! Click one of the buttons above to easily share on Twitter, Facebook, or email.

- Consider becoming a Contributor for Tipping Points

Tipping Points Magazine amplifies the diverse voices within the Self-Directed Education movement. The views expressed in our content belong solely to the author(s). The Alliance for Self-Directed Education disclaims responsibility for any interpretation or application of the information provided. Engage in dialogue by reaching out to the author(s) directly.