As we drove away from the event, I felt strongly that I must share what I learned with the SDE community at large– so much so that I asked and kindly received permission to post the words of those women here. While the transcript below is long, I cannot think of any other way to share it that would do it justice. What follows is the unabridged transcript of that morning panel, and the biographies of the panelists.

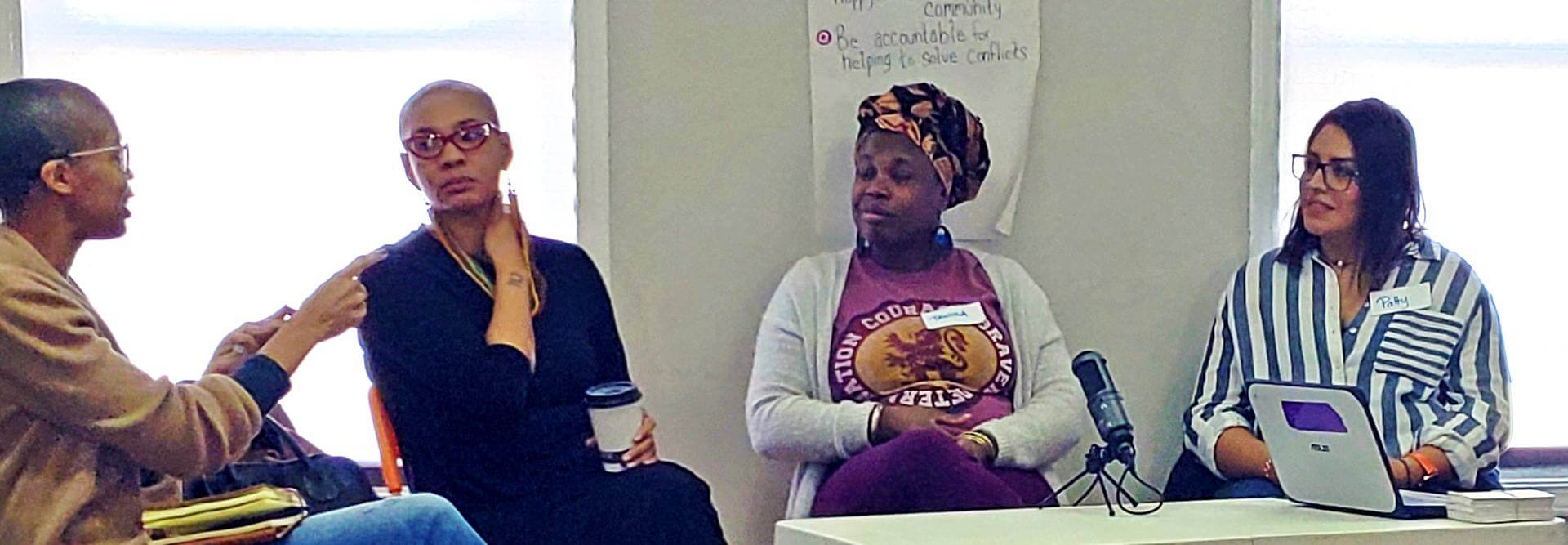

Kelly Limes-Taylor Henderson [moderator]: Hello, I am Kelly Limes-Taylor Henderson. I am not a facilitator here, but I am Heartwood parent. And so, I have been asked to moderate with our wonderful speakers today. It is going to be my first time moderating, and so y’all are going along on this ride with me. But it’s going to be great, and I’m honored to be here. So we have Maleka Diggs here, we have Tamika Middleton, Patty Zavala who are going to talk to us about racial equity and SDE–of course broadly because that’s the topic here– but then just their own pace with that topic. So we’re going to get started, and rather than doing kind of the typical bio like, “this person does this and this person did that,” I want to start with a question for each of our speakers so you can kind of introduce yourselves not by what you’ve done necessarily but what you want us to know about you, okay? Here’s my question: rather than us doing a laundry list of ways that you are accomplished– because all of you have accomplished so much (you [the audience] should have read that already)– tell us what you love most about yourself and the thing that you love doing right now.

Maleka Diggs [panelist]: I think what I love about myself is my desire not to care more and more as I get older. Not caring about someone’s feelings to the point that I alter who I am. So, I’ve been enjoying and really loving not caring. What I’m doing right now that I enjoy? This really. I really enjoy doing this type of work; I enjoy kind of calling myself to the carpet and being in community and sharing. So, that’s what I’m enjoying.

Tamika Middleton [panelist]: I would say the thing that I like about myself the most is something someone else pointed out to me. It is that I have a tendency to do things that invoke fear but do them anyway– things that are not kind of standard issue. This is how you walk through the world. And I’ve always kind of walked my own path in my own journey of which SDE is a part, but I definitely have been like, “You’re going to have your baby at home? Yes I am!” You know, those kinds of things. And so, yeah, I think that’s something that comes up. And then, “What I enjoy doing?” Right now I am enjoying sinking into myself in a way that I haven’t had the opportunity to for a while. You know, you have kids and you have jobs and you give out a lot to the world, and I’ve been really spending a lot of time sinking into my own self or my own spirit.

Patty Zavala [panelist]: It’s a hard question! I think that what I love most about myself is my ability to change my mind. I think we often get stuck in either our own old ways or our parent’s or our community’s. And being able to listen to what somebody’s saying and saying, “Oh, I was wrong! I’m gonna change my mind.” It’s something that I really value about myself. As a mom, it’s something that I find is one of the most precious things that I can give my daughter– the ability to change my expectations of myself, of herself, of my world, of my community, of my language... my own perspective on myself. I think it’s what has really helped me to grow and feel better about myself ultimately. What am I loving the most? I feel like I’m making a difference in other people’s lives, not only my own, but I’ve seen since I started this self-directed journey. I’ve seen it on my mom, on my daughter, on my husband, on my friends. And it’s nice, it’s nice to know that all this hard work, it’s actually changing the way some people see the world, see children, see themselves. And I’m really enjoying that.

KH: Thank you all for answering the question. The difficulty in answering, “What do you love about yourself, what do you love doing,” seems like it shouldn’t be challenging, but it is, right? It seems like it should be natural and easy to answer it but sometimes it’s not. If we’re moving from the kind of naturalness of this concept of loving ourselves into coming up with quick responses to that, can we move to the naturalness of Self-Directed Education or unschooling? How did each of you– very briefly, because I know that you talk about this elsewhere and having other platforms but very briefly for everyone here– how did you come to SDE, if that’s how you term it, or unschooling. Again I’m not going to say who should talk first.

TM: I can talk first. My kids are eleven and five, and we discovered unschooling when I was pregnant with my eleven year old on mothering.com message boards, if people are familiar with them? I used to kind of scour them when I was pregnant, and I was like, “Oh, this is fascinating!” And there was this concept on there that unschooling kids don’t have the pressure of seeking outside validation for the things that they’re doing. And so, because I had always been a kid who had excelled really early, there was always the outside pressure to continue to excel. And then if I didn’t feel like I was good at something or I was going to excel, then I was shut down, and I would quit. And I’m like, “I don’t [want] to do that to my kid.” So we started from birth, you know, always lifelong unschoolers and really whole life unschooling. So like, “we’re not going to do bedtimes, we’re not going to force you to eat things,” and it was a journey. I’m an organizer by trade and by passion; I’m a community organizer. It’s both what I love and what I get paid to do. But very much rooted in tradition of Black liberation. And it felt very much aligned to think of what the power dynamics were inside of parenting, how we’re replicating power dynamics that existed in the outside world, and how if I’m going to dismantle– if I’m spending my life dismantling these power structures in the world– what kind of hypocrisy or cognitive dissonance exists if I’m replicating them inside my home? And when it was time to put my kid in school, at that age when you’re like, “Oh should we go to school?” was at the same time that the Atlanta teacher scandal was happening, and I was working at an organization that was doing this work around race education specifically with young people, with young, Black children. And there were all these school closures that were happening, and we were having all these conversations about the racial dynamics of Atlanta public schools and about the racial dynamics of this scandal and both– not only how Blackness impacted the students inside the school system– but also how it impacted these teachers. And I was just very much not willing to subject my kid to that, to subject my little Black boy to that kind of structure– my very active, very independent child– I didn’t want to do it. And so, we stayed with what we were doing because it was working.

PZ: I actually think it found me. I was pretty ok with conforming with everything. I mean a part of me was like, “I shouldn’t be like this,” you know. But I didn’t know there were options, and I was reading– I’ve talked about this– I was reading the Stop Stealing Dreams essay, if you ever find it online. And it sort of talks about school as a system of oppression. And when I read it I was like, “Oh God, it’s true!” It was almost heavy, shocking to see how little I realized, all of it. At the time, my daughter was three, and we were starting to look into schools. And my first reaction, after running to my husband and showing him like, “you have to read this,” was, well you know, “that’s great for some people, you know... yay!” But then, the more that I sat with it the more uncomfortable I felt, and the more I started to peel back into that, “Uh!” I was really so inside the whole system. I didn’t even notice it was a system. And then I started reading more, I started reading more about schools. I found out about Sudbury. And it was sort of a leap of faith. I have to say, I wasn’t convinced when we started unschooling. I was sure that we were gonna homeschool because the curriculum needed to go in, and you know, freedom to play– some other time. It’s been a shocking journey for me. It was easy for my daughter, you know, this just feels good. For me it was hard, it was hard to change my expectations. It was hard to accept all the things that I had already been doing wrong. Oppressing. It was hard to say, “Yeah I made mistakes.” It’s been a weird journey where there’s a lot of doubt. But every time that I for any reason [have doubt], my faith in it it just calls me back. It’s just like doing it right– this is the thing. And as I mentioned, I’ve seen it impact all aspects of my life. And it started there, it was a spark there– that I feel it’s been like a revolution for me, which ironically I chose as a school for my daughter, and it became my lifestyle. So, I think it found me.

MD: Homeschooling was not a word that I was familiar with at all, at least, not in a positive context. As a person who came from a background in corporate America, in art and design, and I would have to hire people, and as soon as you saw “homeschooler” on the applications, [you thought], “you’re gonna be smart but you’re socially inept.” You know, it’s, “how can you sell this product?” That was how I was introduced to homeschoolers. So the notion that home education is an umbrella to many other forms of learning wasn’t something that I understood until I was forced to. So, for my daughters I was definitely the parent who moved to a neighborhood that would place my daughters in the catchment of quality education. This location is definitely filled with people who don’t look like me, but the school does which is its own type of math and nothing of what I felt connected to. But as a parent you’re willing to do just about whatever to ensure that your child is going to have this fabulous, great experience that will lead them into being successful adults, like skipping ahead from birth to adult– you’re going to be good. But, I did that move, and I looked at the school and said, “All right it’s a public school, it’s free.” Those are two things that I love, I’m a product of public school. So I figured even though in my core I’m an unschooler, I just figured, as a young person you don’t really get a say as to how you learn. This is just what you do, you follow this regimen, whatever. Apparently parents are always right. So I did that, and I stepped into the school, and I brought all the information with me. And this was for my oldest daughter now who is 13. And I have all my information and– you know when you’re at the bank? I’ve been at the bank a lot of times, and I’ve gotten the check and there’s a moment where the teller walks away with your check, but they don’t they don’t cash it and you’re like, “but...?” You know, it’s like that pause where you want your cash, and you’re like, “What’s wrong?! This is a legitimate paper.” You know, that’s how I felt at the school when they were taking my documents. And they took my documents, went back to this room that I knew nothing of, and it was like, “What’s the problem?” The principal comes out and asked me for a seventh form of identification. There wasn’t anything about what I provided that was inconsistent. Nothing at all. She proceeded to ask me if I used coupons to pay my rent because the neighborhood that I lived in was not a neighborhood that people like me live in by and large. So, that was the first time my daughter was seeing me in a moment like this. And it was a really hard decision, but it was that moment of, “Do I allow this? Do I allow this to happen? How can I advocate for my children?” Because this is something that they’re going to experience consistently. What message am I sending if I don’t say anything about this, whether they’re cognizant of what’s happening or not. The notion that I’m just going to kind of curtail and just handle what has just been told, and I’m like, “No!” So it got pretty lively in the school. And– she’s the principal of the school– well, if you’re the leader of this institution, who are you hiring? And who are these young people looking up to as an example? Like whose modeling something that’s worth modeling that’s going to produce positive results? So, I reached out to the school district. I let them know what my issue was and they said well, she’s... what did they tell me? They told me she’s just having a “rare morning.” It’s like, Falling Down like Michael Douglas rare morning? Because I was feeling like falling down and rolling back prices. But, yeah, so they really just sugar coated the entire experience and really put the onus on me if I wanted to move forward. But they just told me it would be more work than it would be. So my big kind of F you to them was like, “I’m not sending my kids anywhere near here.” And that’s just kind of how we started. But it was definitely a journey, but yeah, it found me for sure.

KH: The three of you– either, kind of overtly or through your own observation of research–you all make the connections between schooling and oppression, just generally– or again– on a one on one basis. And at the same time, just like in any oppressive society, minoritized groups will use an institution in order to access resources. You know that the situation is messed up, and also you need to eat, and also you need housing, and also you need safety. So how do you all reconcile the fact that this is an oppressive institution as you are / if you are part of communities that have used the same institution, to access resources. How does that work?

TM: Yeah I mean absolutely like I’m from rural South Carolina. I’m from the South Carolina Sea Islands, and I’m from a very small community. And so, [in] my elementary school everyone was Black. The principals, the teachers, for the most part, everybody was Black, and I felt loved on. And then, you know, I went to middle school, and it wasn’t the same environment. And I went to high school and it was even worse. But I also come from the home of Robert Smalls, and for people who don’t know who Robert Smalls was: Robert Smalls was an enslaved man who was from Beaufort, South Carolina, but then was enslaved in Charleston and stole a Confederate ship and turned it over to the Union was able to free several people, went on to be a state a state legislator in South Carolina, and was very much advocating for public schools so that black folks had access to education. And so I grew up in this place where this man where, you know, one of our middle schools was named after him. And it’s a big thing that Black folks in our community have fought for that access to public education. So, I have a love-hate relationship with schooling. I definitely had a wonderful experience in my elementary school that was actually very much rooted in Blackness, like we had folks from Sierra Leone come and tell us how we were connected to them, and how we were the same people. So I had this very very rooted elementary school experience. And so, I definitely have an understanding of and an appreciation of that. And I also know all the ways that Black folks have had to fight for access to learning and create alternative institutions. And so because Black folks have this history going all the way back to midnight schools during enslavement, we have this history of creating our own institutions for learning. We’re not dismantling public schools today, and we can create other ways for us to exist at the same time. And so I feel like that is what I hold: some of our kids are going to be in public schools right now. It is just what is real and what we have access to, and there are ways and there are folks who are inside who are fighting for it. And in my organizing and my activism work, there is definitely some work that is around how we make public schools tolerable for young kids of Color and simultaneously how do we build alternative institutions so that as we dismantle, we are also building. You know what I’m saying? So, I do have this kind of this tug– you know, push and pull with institutions. And I know what my kid is already doing; he’s like, “I’m gonna go to Georgia Tech,” and I’m like, “Okay, for what?” “I don’t know.” And that’s what it is, and I’m like, “Okay, so we’ll get you ready for that if you decide that’s what you’re going to do.” And I know that institution is useful. I was a student, and I was like, “Oh I love school. I’m great in school. I love school.” And so, I understand it. I understand the usefulness of it, and I understand that we have to build something that’s better. And we can’t tell people to leave until we have something that’s better, right?

PZ: We moved here from Mexico about three and a half years ago. I used to work full time back in Mexico. We moved here for a job offer my husband had, and I started looking for jobs here. And I would get interviews, I would get calls and then they would meet me. And that changed everything– from the way they would treat me on the phone interview, when they heard my accent or when they saw me, and I wasn’t getting hired. It was maybe a year and a half of rejections before I realize that even though I attended one of the best universities in Latin America, I wasn’t getting hired, and I had to face the fact that I also had a female Mexican brown girl. And what possibilities? You know, it’s beyond the degree you own. She might as well be happy. I actually enjoyed school because, I have said, it’s a lot of indoctrination that you don’t even see is there. So I loved it, and I looked for validation in my teachers and my grades, and it was good for me at the time. But in hindsight, I wasn’t happy. You know, I was doing all right, I was coping. It wasn’t a particularly joyful experience where I said, “You know, I want this for my kids.” So if the degree is not working anyway, and the happiness factor wasn’t there all along, you do you. You find out what you want, and if you do so and when you do so, you’ll pursue something you’re so passionate about you won’t worry about getting hired by the wrong person. You’ll worry about your own goals, whether that’s a financial goal, whether that’s a status or a person or career. So, in that sense it was easier for me to opt out of all these resources. And then when you add on top of the fact that I’m living here, and I think I’m trying here, even though I did not receive the same education that a lot of people here [received], about geography, history, whatever– everything was so different for me. And I’m doing so well, and I’m doing so well because I let go of all those things that I thought I needed. There’s still great access to a lot of resources: smartphones, computers, libraries. And I think it’s way more valuable to– as a human, not only a child, but as a human– to learn how to pull from those resources when you need them, when you’re curious about something, and you’re driven about something, then it’s a great time to to reach out for that– a library, a degree, a university, a Master’s. But it’s very different when it’s self led and self driven than, “This is what you gotta do if you ever want to be happy.” I think you should be the other way around– you should be happy, and if you ever find something else you want to do then go for it.

MD: I hated school. I hated everything about it, but I love to learn. And there was not a space in communities that I was in that held those two in two different ways. It was learning and it was education, and it all happened at the same time, and it happened in a particular way that did not have me in mind. So the glass ceiling the idea that if I work in a bootstrap mentality or if you work really really really hard and you just happen to be light skinned, this is it. But then other people around me would have different skills. So, I always questioned the idea of school, I just never fully understood how to articulate. It just never felt good. So the idea now that everything just kind of came full circle when my daughters had that experience, and then I experienced it with them I’m like, “Oh my gosh, that’s like 30 years later, and they’re literally living my faults.” I didn’t experience what they experienced but my thoughts they experienced. So, that for me changed everything. I get the idea of school, and I think in theory it’s lovely. But it is not equitable and that really for me becomes the issue. How are we allowing young people to really learn on their terms? And how engaged can parents be, if they too have been conditioned to a particular set of mindsets, that define what learning is and the way it should be achieved. I don’t know if Atlanta or Georgia is experiencing this but there are a lot of folks who are wanting government assistance for homeschooling families, to get a check so that we can purchase– and I vehemently say, “no” for me. Because that means now you want something– you want me to be under the scope. And because we are self-directed, because we are unschooled, I don’t want to have to write off the fact that I had to buy some chai for my daughter’s project– that’s just what it is. And I don’t want folks to try and capitalize off of something where you’re just going to use it as another symbol of oppression. So, I reconcile it by saying, “Fuck you. I’m just going to do me and– you can try– but this little home right here wants no parts of it.” So, I get it, but I want no part of it.

TM: It really resonated– especially when you were talking about different people having very different stories– because I think about, for me school was amazing. And I also recognize that not everybody had it– even inside the same school that I was in. I grew up in rural St. Helena Island, SC where there was corporal punishment in my school, and so, not everybody had the same experience. But I also was thinking about this idea that it’s not really necessarily just about the institution of the school itself or the institution of schooling largely, and how– even as I felt very very loved and nurtured inside of my own elementary school inside of my very small insular Black community– we were still a part of this larger institution that I can vividly remember trying to dismantle, the school that we were in. And I remember when I left– when I was older– that there being such an attempt to dismantle the school that there were massive protests– they were trying to push out the principal who had been there, who knew every single student, by name, whether you had graduated, or left the school ten years ago or not. Such massive protests that Danny Glover came out protesting with us about the attempts to get rid of the principal and all these black teachers and everything. And they were successful, and so [now] it’s a very different school. Even though we’re on this island that is 90% Black, the principal is White and most of the teachers are White– even though almost all of the students are Black. And so, in spite of this institution of schooling, even if you have a safe space it’s not necessarily always going to be safe. There’s always going to be this this kind of oppression that exists inside of it; it’s not always going to be safe. Even at the elementary school level we all had very different experiences, whether you were at that school, or a different school, or even inside of that school. Even as we use those resources, even as we make something out of those resources– we might get a grounding in our Blackness– there’s always a route because we’re inside of this larger institution of schooling but also inside of this larger system of White supremacy, this larger system of capitalism that is constantly bearing down on certain groups of folks. And so, how we build institutions that are outside of that system, how we build lives that are outside of the system, how we don’t allow those systems to encroach on the institutions that we build in on our own lives, and how we say, “Well, we don’t actually want government funding because with government funding comes strings and with government funding comes government problems.” And government problems disproportionately negatively impacts certain groups of people. And you don’t even have to look at just schooling like that– I’m a student midwife and a lot of what I’ve studied is the history of Black midwifery. When you look at the moment that folks are like, “We want the government to regulate midwifery,” you have the eradication of Black midwives. Whenever the government intervenes on the systems and institutions that Black folks and Brown folks and Indigenous folks build in this country as a way to survive and to resist oppression– whenever the government encroaches on that– you always see the dismantling of those institutions, you see increased surveillance in ways that are detrimental to our actual survival, our actual sense of who we are as people, our connection to each other as a community. When we access those resources there’s always a catch there’s always a rub.

KH: So, with speaking to that rub, because if we are in– and not “if,” as in “I’m not sure,” I am sure– if we are in a White supremacist society, then the government is going to uphold it– it has to, it’s going to this society. Whatever you get, however you engage with this dominant society, if you are not a White person, sooner or later you will lose– because it’s not for you. You can access it– if you can– but in the end– you, in this body that you’re in– it is not going to be for you. And you’ll find that out sooner or later. And keeping that in mind– because I just can’t get it out of my mind– [looking to Patty Zavala], “she might as well be happy.” I can’t get that out of my mind because it’s like, “This is not going to work. I got what I was supposed to get out of it, and it’s not working because of this dominant structure.” My child might as well be happy– that statement feels to me– if it is coming out of the mouth of Indigenous folks, Black folks, Brown folks– that’s some revolutionary shit. “She might as well be happy.” Keeping that in mind, what about SDE, what about unschooling is particularly revolutionary, in your opinion, when it comes to our Brown children, our Black children, our Indigenous children?

PZ: I think it even builds on what you were talking about. For me– [the] Spanish conquering Mexico and the Indigenous [people] and throwing away their religion and their languages and “You don’t do this, you do this”– that fits with me. From there until today, you’ve got to follow the money: who’s benefiting from this oppression? Because it is still happening. Who is benefiting from me not getting that job? It’s not about women. It’s not about Mexican women. It’s not. Who is benefiting from dismantling the safe spaces? Who’s taking this place of power of deciding what kind of curriculum you learn? In Mexico, the public school books are all issued by the government. I don’t know how you call that a democracy? Because you’re literally printing the books that you’re using to teach the kids– and through the lens that the government wants to give to you. To me, that’s a core concept of unschooling as a revolution for People of Color. It’s no longer about whose land you’re being given or who is editing the book that you’re reading. It’s about you having the ability of saying, “This is where– I’m going to read this one too” without needing to move on to the next assignment and being able to spend as much time on the topic as you want, exploring all different points of view– because there’s no such thing as one correct and one incorrect. And yet that’s what we teach– literally. This is a test and you have to tell me which one is correct and which ones incorrect. When we teach young people to be able to discern, to be able to watch a TV show and say, “That’s odd that shouldn’t be like that,” or a book or a magazine or a podcast or another person and being able to call out on that person, to call out on the book, to call out on themselves– that’s the core of a revolution of why it’s going to change education– the way that they see it– because it’s no longer, “I need to be taught,” and, “I need to go to this institution to learn.” It’s about taking control and choosing your perspective and choosing your own personality at the end of the day because when all of that information that you get is force fed, it builds who you are, your identity.

MD: For me, simply it’s unschooling is that we can. It’s not even a question of, “Is this possible?” It’s something that for me and our family shows itself in real time, that it is. And if I’m functioning with a schoolish mind, that is something that you work to attain to– if you do these particular steps and posture yourself to whomever is dictating that for you that mysterious cloak behind the dagger. So, it is that you can... I always have these random shower thoughts, and something that I shared on Instagram was: liberation will always appear uncomfortable to the indoctrinated. I love that. I love being comfortably uncomfortable and uncomfortably comfortable walking in the presence of my own liberation. If my movements in any way make me appear– like, “objects can be closer than they appear”– like if my liberation is hitting you in a way that makes you uncertain, then I can. What I am doing is literally working in real time. If it’s gonna make you pause– I don’t know why, mind your manners– you just can, simply. And it’s just not something that I experienced in brick and mortar, from a traditional standpoint, so to speak. And that’s not what I’m seeing [with] young people– they’re more often than not told that they can not. I’d much rather be in a space where [it is], “Because they can.”

TM: Across town, I am a part of building a space that is a Self-Directed Education space and there are whole bunch of organizers. And we’re like, “We’re the organizers, we’re going to build this space. We’re going to be in the Black, queer, radical, feminist tradition. This sounds great! Let’s bring all of these organizers, everyone is going to be liberated!” And we found that SDE is a hard thing for people to grasp. One of the conversations that we have is, “You’re spending all of your days talking about how we are going to get Black people to freedom, right?” That’s what all of us in our day jobs– and all the things we do outside of our day jobs– that’s what we’re doing. And so we say, “What does freedom look like?” And people are like,” I don’t know. We don’t know until we get there.” And I’m like, “But we can know, right?” How can we create a space where our children are able to experiment with what freedom looks like? How can we create a space where Black children have the opportunity to be free– so that we can model Black freedom. We can model Black liberation in our space, and if we can do that then we have a template. We have some direction for us to follow, some things that we had not contemplated in our battles that we can start moving through in our work– so that we can actually have it for all of us. That for me is what is revolutionary– [it] is that when my kids are in a space where oppression is happening, they can recognize it because they know what it means to feel free. And what I know to be true, what I see in the world, what I see on social media is that often Black folks, Indigenous folks, People of Color sometimes have a hard time recognizing when they’ve experienced oppression. Sometimes you’ll be like, “Yo that’s racist nigger!” And they’ll be like, “Is it?!” “Like yeah, actually it is! It is!” Well, part of that is because we tend not to have conversations about what racism is. Racism is a hard conversation. Lots of people circle around it. But when my kids know what it means to feel free, then when they go to a space or when they witness something, they’re like, “Actually that’s not right.” [They] will tell you that that’s not consent. No means no. They’ll tell you that quickly. My kids will see something happening with a child and they’ll say– my daughter has said in front of people, “Parents are supposed to love their kids.” To another parent! And I’m like, “Oh shoot! Yikes!” What do I say! Because they have experienced, they [say], “You owe me an apology. I don’t care how old you are– you owe me an apology; that wasn’t right.” They know what it means to live in freedom, and so, when they are in the world, they feel what oppression feels like. And they have the confidence and the tools to address it. They have the confidence that– no matter what your title is, no matter what position you hold– I can actually address that. Because, if I can address it in my household with my mama and my grandmother, then I know I can address it out in the world with you. And I know that those folks are going to have my back regardless. And so, I feel like that is revolutionary. When I was pregnant with my oldest, I used to work with this family and they had a daughter who was on the autism spectrum and they hired a grad student to come in and facilitate with their daughter [with] this particular kind of therapy. And one of the things that they would tell us is they would say, “We don’t ever tell her no. We try to figure out how to get to the thing that she wants.” And I remember being like, “That’s some White shit.” Black folks don’t have that experience of, “You never get told no? You just going to figure it out?” That’s not how I was raised. I remember going home and telling my husband, and he was like, “Yo! I imagine how the world is opened up to you if someone’s like, ‘It’s not a no. Let’s figure out how to get there. Let’s figure out a different kind of plan to get you there.'” That was a mind boggling. And so, when I when I started to read about unschooling people were like, “Yeah, it’s not about compromise; it’s about saying how everyone can get the things that they need. And what you see as a want might be a need for this person. So, treat it in that way.” And I was like, “Oh my god! I can do this with my kids?!” You don’t have to have money to do that– you can figure that out. And I think that is revolutionary because it opens up the world in a different way to children, for whom the world is often very closed. So often Black folks have to tell their kids how to navigate the world so that they are not damaged. And so often what that means is putting on all of these restrictions; it is telling your kid how to be smaller. I know so many little Black boys who are busy, they are physical, and when they get into schools they learn to shrink themselves. And then when they get to be teenagers and they know, “I can’t do the same things my White teenage friends can do.” And they shrink themselves again, and all through life we’re shrinking ourselves, we’re shrinking ourselves. And I’m teaching my kids how to be big, be full, be all the weight in your body. And I feel like that’s revolutionary. I feel like that is something that we don’t get and it has the potential. I feel like what People of Color haven’t been able to do when we’ve been shrunken has been phenomenal. Imagine what we can do when we are allowed to be our full selves.

MD: The beauty of this is in building on that notion that you’re in just the reality that your children can call that out. They’re going to call a spade a spade if they see it, and having that hard conversation with your young people about the fact that, “I understand sweetheart that your friends are White– and that’s cool– but please bear in mind that you and your White friends need to understand that if you are in in danger, everybody has got to be on the same wavelength. That advocacy has to happen in unison. And it doesn’t matter if it’s not uncomfortable for your White friend. Your White friend has got to step up, and not put them in a space of feeling like they’re in danger.” The idea that my daughters can now have those conversations with their White friends and they have their way of doing it like, “Yo, Sarah listen, we’re going downtown.” “Ut uh; We can’t. These are things that are not okay, and these are things that put me and my safety in danger, and no one wants my mom to come downtown. Let’s turn all of this into something that benefits us both. And that may mean that you may have to sacrifice something of who you are, a privilege of who you are. And that’s okay because at least in that very moment you get a little taste of what it feels like to be me.”

PZ: I just had a bit of an “aha!” moment myself when you were talking about the reasons that the unschooling or Self-Directed Education, it’s revolutionary. And you mentioned the discomfort that other people feel. And I don’t think until now I had realized how my six-year-old saying to an adult, “I don’t go to school; I don’t do that kind of thing,” how she’s so used to causing discomfort. It’s preparing her as a Person of Color to cause discomfort. It disrupts the way that you know. So what? “Your discomfort is now your issue, not mine.” And up until this moment I hadn’t realized how that is also preparing her to be a woman and a Woman of Color in the world. It’s revolutionary.

TM: That made me think of my work. I work with domestic workers, Black women who work in other people’s homes. And we do a practice called somatics— are people familiar with somatics? One of the things that’s so interesting for me is, when we’re dealing somatics, one of the things that we say is, “Make yourself wider. Make yourself taller. Take up space.” And the level of discomfort people have with taking up space because they are so used to not wanting to make other people uncomfortable. They’re like, “I don’t want to brush up too close against your energy, to be too wide because of how uncomfortable that might make other people.” In a program that I went through, they were telling us that one of the Black men in the program had an actual physical reaction to learning to lengthen himself and stand his dignity. Because as a large, Black man he had so often had to make himself small so that other people would be comfortable, so people would not be uncomfortable with his Blackness and with his size. And so, how we are teaching these children from the youngest ages to make people uncomfortable, like don’t shrink yourselves so other people can be comfortable. Don’t not be true about who you are and what your life is so that other people can be comfortable. And I just feel like that’s it. That’s the key.

KH: They’re not even necessarily processing that they’re making other people uncomfortable cause it’s never been their problem, right? They’re not being taught that it is their problem. A lot of us have been taught– a lot of us at this point can sense it. We know because we’ve been taught over time how to shrink, how to read the room, read people, train ourselves. And our kids don’t even have the question. All right, so we of course can talk about how the work that we do– because I think what unschooling and SDE and the work of it maybe pushes back against schooling as an institution that sort of thing. And that’s fine. My last question is that, exclusively in the work that you and your family, your communities do around SDE or unschooling, how does Whiteness bump up against that? Not in a kind way like, “Hello, I’m Whiteness.” If it happens, how it happens, how does it work against the work that you do as someone that practices SDE and unschooling and also a non-White person. How does Whiteness bump up against what you do?

MD: How does it not? Culture clash for sure. As an unschooling Black mother who’s very much rooted into her culture and encountering White families who are like, “Oh, we unschool too!” Like, “all right...” “Oh he’s hanging off the rafters!” “You don’t want to [motions to come down]? ...okay...” There’s just something that’s different in how that communication happens between me as a Black woman with my Black daughters and their father with his Black daughters. There’s something in the space for me that creates a bit of a friction because... in certain cases, it almost allows for things like color blindness to be okay. Because folks will see you and you’re like, “Well you do what I do, so thus we’re the same.” Well, like, no. You literally can get up freely and do whatever you choose to do as a White person period. You just happen to be unschooling. It’s almost an oxymoron, like the freedom is there to explore. If we’re talking about liberation, you don’t have to have that title as a White person– you just– BAM, it’s there. Now, everyone’s situation is different for sure, and maybe people experience things on a higher level. But this isn’t a method. This is a lifestyle that we’re choosing to engage in that pushes the envelope of what we’ve been conditioned to believe about ourselves. So, if I’m going to have White folks come into my space, it is a privilege for them to be there, where, for me, it is a liberating experience. And I think the two can clash, and knowing when to pause in those spaces– because sometimes that pause is necessary for safety, where that’s not something my White counterparts would have to think about. I have to remember that yes, I am doing this work and it is really intentional, but my life still means less in a very grand scheme of things. So, for me culture does play a large role in it– calling yourself unschooling, radical, self-directed those are all great terms– but we still live under an umbrella of a system that just says, me, looking the way I look, is gonna have a treatment that is less than what you’ve experienced and also less than what Tamika will experience, and different than what Patty will experience. So, if we’re going to come together, that has to be understood that there is still culture that has to be taken into consideration if we’re going to have these conversations, if we’re going to share space together, it’s not just about privilege. It really is about liberation.

TM: I will name upfront, that we’ve created a pretty little Black bubble over on the west side of the city. And honestly we don’t in our day to day come up with it– we live in East Point. East Point is like 70 some odd percent Black. We do most of our organizing, most of our homeschooling stuff in the West End– which is gentrified but is still heavily Black– and in the Pittsburgh neighborhood which is also gentrified is still heavily Black. And so, there’s not a ton of times when we’re confronted in our day to day where we had this experience. What I will say is, early on I didn’t know any Black unschoolers, Black homeschoolers, and I used to live in the Yahoo groups. And you know there weren’t really very many Black people people inside of those groups. And so, sometimes I would read some of the some of the advice and be like, “Oh....” There were some things where they were like, “You don’t have to do this, because it’s only going to be an issue if someone reports you to D-FACS [Department of Family and Children Services].” And I’m like, “The chances of somebody reporting me to D-FACS are not that low, you know.” In my experience as a Black parent living unconventionally with D-FACS is going to be a different experience than a White person. So, often there are things that I’m more careful about because I’m conscious of the fact that I am Black everywhere I go. And sometimes I recognize that in those dialogues there are things that White folks are not thinking about that I am absolutely thinking about in the ways that I allow my children to be free. But I’m also always a shield to protect that freedom. And so, I’m having to be vigilant in ways that I recognize that a lot of White unschooling parents are not having to be vigilant. Even like, we’re in the airport, and I’m like, “Oh your kid is running behind the ticket counter.” Because I know that I’m going to be judged in a particular way. Inside of the freedom that my kids have, I have to have conversations with my kids that I know other folks aren’t having to have. So, often the advice that I would find in the Yahoo groups, I would read, but I would never ask questions. I would never ask for advice. So I had no idea but the advice that I’m getting is not going to be relevant to my lived experience. It is going to be interesting, it is going to be a way to open up the way I think about unschooling, but it’s not going to be relevant to my lived experience at all. I think that that is super apparent, and I also think that the ways that, when you talk about homeschooling advocacy generally and people try to get certain laws passed– just like you were saying, advocating for certain things– there’s a recognition that there’s not a race analysis or a class analysis inside of what laws people are advocating for, what ways people are advocating for access to certain resources. When I look at what’s happening on a national scale I’m like, “Oh!” There’s not a race and class analysis outside of what you’re asking for because this actually will have a negative detrimental [effect] on certain communities of people and certain groups of folks. I think those are the ways. I’ll be honest, we have a very Blackity-Black experience.

PZ: It’s hard, sometimes you get heated up in an argument and then somebody tells you, “this is not about racism...” No, no you cannot really separate one from the other. And that applies to being White or non-White. You cannot separate who you are, and what your body is, and what it looks like, and what your culture is from everything– from the way that people see you, from the way that people talk to you, from the way people perceive what you’re saying. There are so many biases in everybody; nobody is excluded of them. And I think it often clashes with unschooling. People believe that just because you’re unschooling you’re already doing the work or making a difference. And in my experience, it is not the case. You can definitely be a very racist unschooler. It is not mutually exclusive. That being said, in my personal community, where we spend our time, we have really beautiful interactions. We’ve had– all of the families that I’ve encountered– have had an ability to step back and shut up. And I don’t mean that in a rude way. On the contrary, “Good job. You’re actually being a non-racist unschooler.” I mean, there are layers and there are moments, and we all make mistakes. My personal experience has been really beautiful with my local community. It has not been the same with non-unschoolers; it’s seen as what I am doing, it’s wrong. You already have been dealt some hard cards. “You should definitely climb the traditional ladder if you expect any of this success.” It’s hard with friends. It’s hard with friends who cannot get past their biases and see deliberate reasons about what we’re doing. And when they’re not able to to realize that education or growing or liberation– it is all together– it is not only a school choice. It is not like public school A from public school B. It it is radically different and it goes way beyond standardized testing, which is where some sometimes they get stuck. But yeah, I think it clashes both inside the unschooling community but outside too. When people are not able to see the difference. I cannot separate myself from race. I cannot stop thinking about it. I cannot see it through a different view because of the way that I’m going to get treated, because of the way that people believe things from me, because of the way that my daughter speaks English with, well, not much of an accent... it’s her native tongue. They just immediately assume that I am the nanny. And because we are unschooling, they just assume that I am the homeschooling teacher, and then they just start giving me advice about like tests and like... “I’m just chillin’ in the park, you know?!” So definitely it’s a cultural clash. And I think, even though it is not my job as a Latina, as a Person of Color to educate them, it’s something that I’m finding joy in– even though I don’t feel the responsibility. I feel that I’m able to opt out and feel like, “I don’t wanna have this conversation with you,” and I’m out. I’m enjoying those times when people actually listen, and they’re able to change their perspectives.

TM: I’d like to just raise up folks in this room and out who have a lot of these conversations inside like Julia, Anthony, Patty, Kelly, Akilah– like tons of folks that are having these conversations. I do remember like ten years ago when they were unschooling groups and there were no faces of color. And I’m like, “I’m not going to that, it’s going to be all of the White people!” And it’s so good to see that when there are conversations about unschooling and conversations about SDE, there are people of color who I see, and I think, “Oh, this is a really different world than it was when we started out.” And so, I just want to raise up and appreciate all the folks who are doing that hard work of moving those conversations.

Panelist Biographies

Maleka Diggs is founder and owner of Eclectic Learning Network (ELN), a secular, Black- and Brown-centered home-education network in Philadelphia, PA. ELN is dedicated to empowering families and learning institutions through community, connection and awarenesses that reflect the cultural and interest-driven needs of young people. Maleka is an unschooling mom of two girls, 11- and 13-years old. She was recently featured on an NPR Episode, and has also been interviewed for Akilah Richards’ Fare of the Free Child podcast.

Tamika Middleton is one of the founders of the Anna Julia Cooper Learning and Liberation Center, a cooperative, learner-centered, and self-directed community rooted in a radical Black queer feminist politic. She is the Georgia State Director of National Domestic Workers Alliance. She is an organizer, birthworker, writer, and unschooling mama. She is passionate about and active in struggles that affect Black women’s lives. You can read some of her published works over at Change Wire. Tamika was featured in Episode 1 of Akilah Richard’s Fare of the Free Child podcast, Unschooling Explained.

Patricia Zavala is a Mexican expat living in Atlanta since 2015 with her family. An unschooling mom, self-taught graphic designer, and marketing professional, she believes in self-directed education as a path of liberation from systems of oppression and a journey of introspection, self-knowledge, and self-love. Patty is a co-founder of Music Unlimited Atlanta, a self-directed, play-based music learning center dedicated to inspire and equip Black and Brown youth to explore their musical education through a joyful, non-coercive experience. Currently, she serves as board chair at the Sudbury School of Atlanta, a democratic, mixed-age, self-directed school. She was featured in an Akilah Richard’s Fare of the Free Child podcast episode titled, Sudbury Model Solution

* I have such awe and sincere thanks for the Atlanta and New York City unschooling / SDE communities and all of those along the way, who opened their homes to us and generously supported us with financial contributions. This trip and this article literally would not have been possible without the support of: the Beckler family; Noah Mayers and Brooklyn Apple Academy; Abigail Oulton; Julia Cordero, Anthony Galloway and the Heartwood Agile Learning Center; Christina Henderson, Kelly Limes-Taylor Henderson, their son Harrison and the rest of their wonderful family; Daniel McLellan and Maria Britton.

If you enjoyed this article and feel called to give back to ASDE, here are ways you can support our work:

- Donate money

- Share our content with others! Click one of the buttons above to easily share on Twitter, Facebook, or email.

- Consider becoming a Contributor for Tipping Points

Tipping Points Magazine amplifies the diverse voices within the Self-Directed Education movement. The views expressed in our content belong solely to the author(s). The Alliance for Self-Directed Education disclaims responsibility for any interpretation or application of the information provided. Engage in dialogue by reaching out to the author(s) directly.