Madison wanted to travel to PRIDE in New York. Her dad wasn’t so sure. So she developed a Powerpoint, sat him down, and presented her argument. Detailing her travel plans, safety measures, and her own competencies, she sized up her audience and won her case.

She tells me this story nonchalantly, as if it were a typical reaction for thwarted teenagers. Having taught more than a few, I would beg to differ.

Madison attended World Pride in New York City. Talking your parents into letting you attend a massive rally is real-life learning. But at Philly Free School (PFS), this is often what learning looks like. Motivated to tackle real-life obstacles, kids invent solutions, develop skills, and devise projects to achieve their ends. In my last post on my blog, I began to discuss the idea of Self-Directed Education (SDE).

The basic premise of SDE that I observed at PFS is that kids determine their own goals and activities. They do what they want, provided it doesn’t infringe on the rights of others. Adults try not to intervene, keeping their own, ‘schooled’ value systems to themselves. If a kid wants to play all day, then play, baby, play.

I’m still struggling with this paradigm.

On the one hand, I hear the argument that SDE risks deepening inequalities. You don’t know what you don’t know. If a kid hasn’t been exposed to the types of knowledge that confer privilege in our unjust world, don’t we have a duty to provide that access, even if the kid has to be coerced into learning?

On the other hand, I hear the argument that we’ll never get to liberation through coercion. If we want to raise people free from our world’s hierarchies, we must let them grow up that way. We shouldn’t allow the realities of late-stage Capitalism and white supremacy to eclipse our kids’ passions. We cannot change the game by submitting to its rules.

I often put it this way: Do we educate our kids to survive in the world as it is? Or do we allow them to imagine the world as it should be?

Learning to Read

One of the most interesting examples of SDE is self-taught reading.

We expend vast resources in conventional schools trying to teach children how to read. We also link future learning to literacy; a child who doesn’t progress from “learning to read” to “reading to learn” will often be left behind their peers.

Forcing kids to read this way often backfires; they get frustrated and develop negative associations with reading. Then they carry that baggage with them. Teaching high school in a conventional, urban school, most of my students were behind “grade level” in reading, sometimes by a couple years, sometimes by many more. Many of these kids decided that they hated reading — as a source of frustration, boredom, and feelings of inadequacy, it was safer to hate reading than acknowledge that reading was difficult for them. In SDE environments like PFS, kids are never forced into reading, but they do learn to read. Each child’s story varies, but most say that they’re self-taught; some learn through video games, some through writing their own stories, and some become motivated to read the first time an adult or older sibling doesn’t have time to read aloud to them.

To get more insight into this process, I interviewed Tahj. Tahj came to PFS with some reading fundamentals that he developed in his previous school, but he insists that he became a strong reader here.

According to Tahj, his big motivation came when he saw his brother reading comic books that his parents deemed “inappropriate” for Tahj. He tells me that this made them all the more appealing: “it was one of those older kid books, and I really wanted to read it.”

Though his older brother would sometimes point out words for him, Tahj insists that he was primarily self-taught. I asked him what he would do if he was trying to read a book that was too hard for him, and he described his process: “I’d usually look at a dictionary. We have a lot of dictionaries. Sometimes I’d ask my mom and dad, but I’d look in the dictionary a lot.”

Tahj still goes to his dictionary when he encounters a new word. He gave me a recent example: “Some of the toys here use really big words. Like, I learned a word yesterday from a Lego set.” He struggles a little to pronounce it: “It was like... philantropist? philanthropist? It was in a Marvel set about Tony Stark. The word means you have a lot of money and you’re willing to give some of it away to charity.” I asked him how he learned what it meant. He told me, “When I got in the car, I asked my dad. To see if he was right, to fact-check him, I looked in the dictionary when I got home.”

Tahj’s story isn’t unique. Peter Gray, a research professor at Boston College whose work focuses on children’s play and learning, has studied literacy acquisition at schools like PFS and has found that children in these environments usually teach themselves to read, often very rapidly, once they decide they want to learn.

Gray’s research also acknowledges that many “self-taught” readers are picking up reading skills here and there long before they decide that they’re literate. According to Tahj’s mom, that was the case for him as well — he even received formal instruction in phonics at his previous school. But research suggests that this explicit instruction might not be necessary for many kids. As long as kids grow up in text-rich environments, surrounded by adults or other kids who know how to read, they will learn to read the same way children learn to speak without formal instruction.

Tahj’s process reminds me of my own gradual love affair with the books that filled my childhood home. But what if kids aren’t surrounded by text and other readers? This is the biggest challenge I see to Self-Directed Education; kids whose parents read to them are at a serious advantage in learning to read independently compared to kids who lack a text-rich environment at home.

Aspects of PFS make inroads on disparities in kids’ access to text. For one, kids are surrounded by books; the PFS library is immense. And unlike conventional schools, where books are often quarantined off for designated times of the day, students at PFS are able to read whatever and whenever they want. Tahj credits this for his recent reading growth: “I think I’ve gotten better at reading here because this is a school about independency. There’s a lot of books at PFS. I can read all those books. I love being able to read whenever I actually want to, instead of having to pull out a book at recess or lunch. At my old school there was only 30 minutes of recess and 15 minutes of lunch, and it was hard to figure out how to fit my reading into that.”

Democratic processes at PFS are rooted in text and fuel kids’ motivation to read. Kids must be able to write in order to independently fill out a complaint about another kid, add a motion to School Meeting, participate in much of the committee work, and read the many signs that other students post around the school to inform each other of upcoming meetings and events.

Preliterate kids and weaker readers are also surrounded by strong readers at PFS. Because kids are able to freely interact with their peers, they have numerous teachers, not just the single teacher sanctioned within conventional classrooms. On my first day at PFS, I saw this type of informal, peer-to-peer learning take place. Sitting with a group of teens, I listened to their conversation range over everything from abortion access to interpersonal squabbles on Instagram. One of the teens vented about the poor condition of the sidewalks in Philly, which spun into a discussion of budget priorities. An older teen said, “well until the proletariat rises up to squash the rich, you’ll have to tolerate those potholes.” A younger teen asked, “what does proletariat mean?” So the group got a primer on Marx.

As I sat listening, I thought about the number of times I struggled to demonstrate Marx’s relevance in my World History classes. Coming from an older student, in the context of Philly’s crappy sidewalks, no one needed to convince the group that Marx was relevant.

Kids at PFS learn from each other more than they learn from staff. And unlike most democratic free schools, which are predominantly white and middle-class, PFS is incredibly diverse. Kids enter the school from a huge variety of backgrounds, bringing with them all types of knowledge. Then they’re free to share this with each other.

You Don’t Know What You Don’t Know

PFS may provide kids with more access to the tools and time needed to practice reading than many conventional schools, but the school still can’t address disparities in access that arise in kids’ homes. A child whose parent reads to them each night will develop the fundamentals of reading regardless of whether they actively pursue reading. A child who doesn’t have this privilege may develop those skills, but needn’t necessarily do so.

I’ve focused on reading because it’s the greatest gatekeeper to other forms of knowledge and privilege. But the question of access holds true for all subjects. Arguably, an advantage of conventional schools is that, in forcing everyone to study a set of subjects, our system aims to expose all kids to the areas of knowledge that confer privilege. A child who would otherwise never encounter Physics can fall in love with relativity; a child who would never undertake any systematic study of History may become fascinated with historical methods.

A phrase that’s arisen many times in my recent conversations with friends is “You don’t know what you don’t know.” Math, Chemistry, and History are all areas of knowledge that brought me joy at various times of my life, but I doubt I would have pursued these areas had I not been exposed to them through conventional schooling.

Granted, I sacrificed other passions to pour my time into these academic pursuits; creative writing, dancing, and music all fell by the wayside. Was the trade-off worth it? I often doubt it. But then again, our world as it is places disproportionate value on the academic skills I did acquire. My so-so short stories may not have conferred much advantage on me when it came time to apply for college.

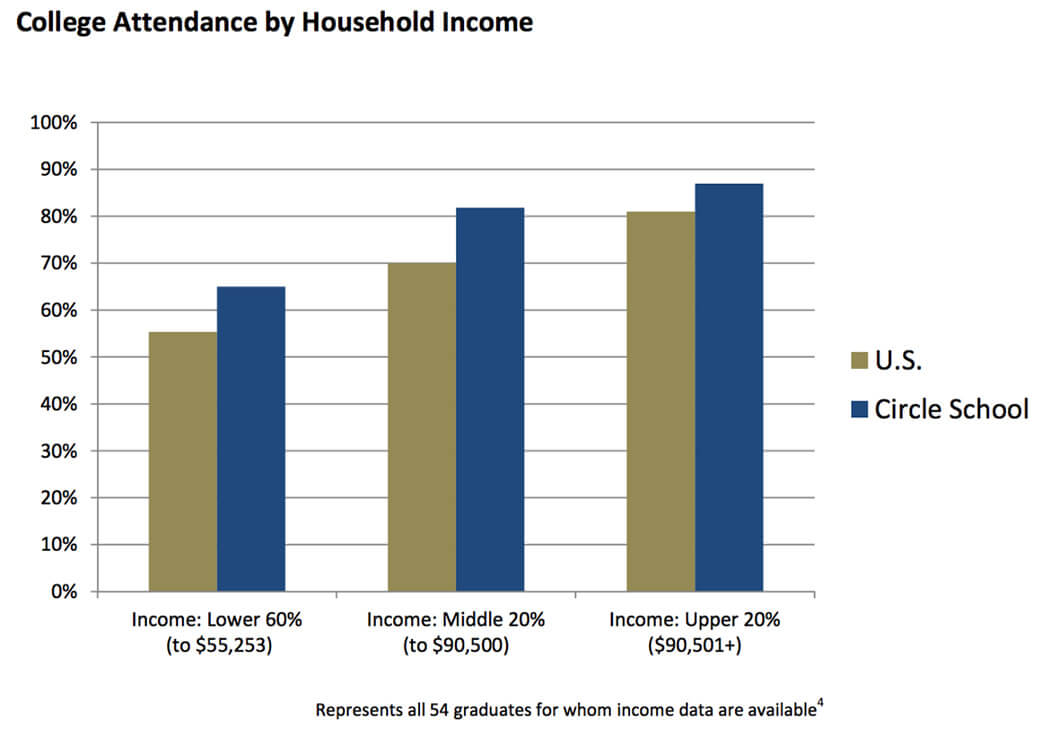

Access to college is one of the first questions I get when I describe PFS, and I always assure people that plenty of students do go on to college. In fact, college attendance rates at schools like PFS exceed national averages. Kids who decide they want to go to college often decide one day to pour themselves into studying for the SAT. Sometimes, that means learning algebra. In those cases, these kids who have always managed their own education pick up a book, find an adult or peer with experience, and teach themselves algebra.

But still, you don’t know what you don’t know. A few days ago, I overheard a student at PFS say that they weren’t going to college because they “couldn’t afford it.” As someone who escaped from a top-rate school with only $11,000 in debt and received upwards of $150,000 in financial aid, this assertion makes my skin crawl.

If college isn’t part of the culture of your family or peer group, it may not seem like a real option. Of course, this issue isn’t limited to schools like PFS. Working in a segregated, urban school, I often heard comments like this from students who were unversed in college particulars like financial aid. But at a school like PFS, no one is making a systematic effort to expose kids to these details. (To be fair, no one is doing that at most segregated, urban schools either, but that’s a failure of equitable implementation. At PFS, staying out of a kid’s way is part of the philosophy.) Kids who are unfamiliar with college might get incidental exposure from staff or other students, but they might not. The practice of valuing all kids’ pursuits equally forestalls any intentional corrections for privileges conferred at home. Case in point: though the Circle School, a democratic free school in Harrisburg, boasts higher-than-average college attendance rates for its students across all income brackets, disparities persist, with wealthier students going to college at higher rates than poorer students.

Democratic free schools and other advocates of Self-Directed Education center freedom and choice in their educational philosophy; children should be free to choose the activities that are meaningful to them. But choice is actually a messy concept. Am I really free to choose something that I know nothing about? Am I really free to pursue a path that no one around me has ever trod?

Deschooling as Decolonization

The flip side of this argument, which gets too little airtime, is that ‘you don’t know what you don’t know’ applies equally to things we don’t learn in conventional schools. Sure, my so-so short stories may not have gotten me into college, but they were my passion, one that I prematurely snuffed out with a hailstorm of advanced academic classes. On one level, this has contributed to my personal unhappiness. On a broader, systemic level, privileging some people’s knowledge over others’ serves to reproduce the inequities of our current world.

Not only the curriculum, but the whole structure of compulsory schooling supports the values that underpin late-stage Capitalism and white supremacy. Offering Western History over Ethnic Studies is just the tip of the iceberg. Kids in conventional schools learn that minds are more important than bodies, that intellectual labor is more valuable than manual labor, that managers are more important than workers. They learn that thinking is preferable to feeling, that rules are more powerful than relationships, that the evaluation of others is more important than self-knowledge.

We are taught that there are a handful of worthy pursuits, that our worth is tied to the prestige of our job, which is tied in turn to our salary. In our schools, and even in my reasoning about literacy and college, the inequities of the Capitalist marketplace are allowed to determine the value of knowledge.

Among socially-conscious educators, we often begrudgingly accept this premise. Knowing that the game is rigged against poor kids, immigrant kids, black and brown kids, we hope to give them the tools to make it within the system. If we’re feeling especially optimistic, we aim to help them see the system for what it is. A friend of mine captured this idea in his classroom motto: “Know the Rules. Change the Game.”

In my history classes, I labored to deconstruct the Eurocentric standards given to me, introduce alternative voices, and offer opportunities for students to expose and critique the status quo. I tried to engineer a curriculum that was both perfectly aligned with imposed standards and authentic to my students.

Yet ask my students how many of them felt my classes fostered their freedom, and I’m not optimistic about the numbers. At the root of it, I was (and to some extent, still am) working within the belief that the only way to revolutionize the game is by submitting to its rules.

The unschoolers I know reject this premise outright. They resist the ordering of knowledge and people into hierarchies. They believe that the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. In the words of Zakiyya Ismail, an unschooling advocate in South Africa, “That the schooling system is fashioned in the image of colonialism is not its worst attribute. It’s real danger is that compulsory schooling upholds and maintains colonialism by upholding colonial values that the colonising countries or settlers still benefit from.” She argues that deschooling is a path towards decolonization. Akilah Richards, an unschooling advocate who pulled her black daughters out of conventional schools, puts the argument briefly: “I am protecting [my daughters] from whiteness.” This sentiment has driven people of color to undertake many community- and self-directed learning initiatives, from the Citizenship Schools of the Civil Rights Movement to the recent uptick in black homeschooling families.

Many Meaningful Lives

The whole argument comes down to this: Is our duty to expose kids to the types of knowledge that confer privilege? Or is our duty to help kids develop into their fullest, most meaningful lives?

Regardless of our positionalities, our choices are limited by our environments. Growing up in a household that was poor but highly and conventionally educated, I squashed my passions for writing, dance, and music early by investing copious energies into study of some academic subjects that now contribute nothing to my daily life.

Speaking to folks around the school, I wonder what my life would look like had I been free to pursue my passions, as so many kids at PFS do.

First there’s Madeline, a twelve year old who attended PFS for eight years. This year she’s decided not to go to PFS. Instead, she’s enrolled in the Pennsylvania Ballet’s day program, where she spends six days each week dancing. Often, she takes the train home by herself, then begins online classes. For Madeline, there’s no boundary between her education and her career. She’s not waiting to begin her life.

Then there’s Jackson, an alumnus of the school. Joel, a staff member, tells me that Jackson spent most of his time in the music room, practicing guitar cycles, teaching little kids to play, and even booking gigs over the phone. While he was still a student at PFS, Jackson’s band was headlining metal shows and fielding sponsorship offers from guitar companies. When he wasn’t playing guitar, he was working at a bike shop, sleeping, or caring for his family. Joel remembers one day when Jackson left school early to translate between a realtor and his Vietnamese parents who were buying a house.

For adults who have been conventionally educated, it’s often hard to recognize kids’ activities as learning. We’ve been conditioned to see value in scholastic, pen-to-paper learning, but left to their own devices, most kids don’t do the things that conventional schools force them to do. They do what feels right to them. Joel credits Jackson for helping him work through some of his own biases: “Jackson made it clear to me that there’s lots of different ways to do self-directed education right. I don’t have the right to evaluate the way anyone else uses their time. There’s so much trust in that.”

If we truly believe, as we often say that we do, that all kids and cultures have valid ways of knowing, if we truly commit to anti-epistemicide as we do to anti-racism, then there is no learning that’s invalid and no earnest life that is not well-lived.

I spent some time speaking about this with Madison, an older student at PFS who attended Philadelphia Public Schools through her sophomore year. For her, access to privilege seems less important than access to meaning, joy, and fulfillment: “I feel like conventional school sets you up for kind of a boring life. So much of your time is taken from you. People get up to go to jobs they hate, the same way they hated getting up and going to school every day. It just carries on for the rest of their life. And that’s really sad to think about... If you’re at a democratic school, you can change your life. I think about a student who just graduated, and he’s going to Italy to work on a farm. Nobody would have done that in traditional school. I guess somebody could have done that, but that’s not something they would have encouraged. They would have asked, ‘Why aren’t you going to college?’ or something like that. When you’re here, it’s like, ‘You want to go to college? Okay.’ ‘You don’t? Okay.’ There’s a lot of other ways to live.”

When I shared my worry about Self-Directed Education, that you don’t know what you don’t know, she saw my point, but offered a counter: “I think that’s just a pitfall of the system that we have. Because sometimes you just can’t shake those notions in someone’s head. We have no system in place to show people that they can do really anything that they want. We have no system to show people different ways of living. But there’s also resourcefulness here. If someone has an interest in something that they aren’t sure they can do, they will often just learn how to do it.”

I asked Madison what she plans to do when she graduates. She tells me that, before coming to PFS, she planned to become a nurse since her public school would have just “shot her into that track.” But now college is unappealing to her; she dislikes school work and has no desire to return to it. Her long-term vision is being an entrepreneur and stay-at-home mom.

Madison ended our interview by reflecting back on an earlier part of the discussion, about the proliferation of urban, high-performing charter schools that promise kids greater access through 100% college attendance: “A lot of families of color put their kids into these schools because they think the only way to have a stable life is by getting a certain amount of education. But there are so many people who have a bachelor’s degree or a master’s degree and they’re barely making money. It’s getting harder. A lot of people are going to have to find ways to make money outside of our conventional systems.”

We also spoke about fear. I’ve heard it said many times that the only reason we subject our children to our modern education system is because we as parents are afraid for them. I think that’s true. But at the same time, some parents have reason to be scared. In Madison’s words, “I think that’s why all those charter schools are so full, especially with low income kids or kids of color... a lot of people are just scared, and they want their kid to be stable when they grow up.”

Like me, Madison sees a tension between access and self-direction, equity and freedom. At many points in our discussion, she wavered, admitting ambiguities and seeing contradictions between the philosophy of Self-Directed Education, the realities of injustice, and the importance of equity.

But when I asked Madison if she’s scared for the future, her answer was decisive: “Mmm... No. Uncertain, yes. But I don’t have fear. I feel hopeful. I don’t know how it’s going to go, but I hope it goes good, and I’m going to make it go good, as much as I can.”

This article was originally published here on October 12, 2019 and has been reprinted with some modifications by permission of the author.

If you enjoyed this article and feel called to give back to ASDE, here are ways you can support our work:

- Donate money

- Share our content with others! Click one of the buttons above to easily share on Twitter, Facebook, or email.

- Consider becoming a Contributor for Tipping Points

Tipping Points Magazine amplifies the diverse voices within the Self-Directed Education movement. The views expressed in our content belong solely to the author(s). The Alliance for Self-Directed Education disclaims responsibility for any interpretation or application of the information provided. Engage in dialogue by reaching out to the author(s) directly.