I rounded the corner in the hallway past the trophy display case in the main entrance of my American suburban public high school. As I neared my locker I saw something posted on it. My heart began to race and my palms started to sweat. Taped to my locker door was a copy of the article I had just published in our newspaper about inequality in our school, about how the football players were treated better than the rest of us, even by the administration. The entire football team had signed the article with their jersey numbers and had written “FAGGOT” across the middle. I scanned the numbers and there it was, even my best friend, who was also on the football team, had signed his number.

Our adulthood identities are built on top of our childhood foundations, they stick with us for better or worse in most of our future behaviors and thought processes: our insecure moments from perhaps years of being labeled one way or another; the people who we decide to trust because they remind us of that first inspiring mentor; the wild chances we gamble because of the things we did and the things we didn’t do in our younger days; and the romances we embrace, built upon from that first time someone’s hand held our hand and we looked each other in the eye and wished that Time would stop.

We left off in Part One of this story building a different foundation, the foundational story of how society develops one’s perception of sexuality and gender within childhood. We reviewed the history of that perception as it was built up and supported in self-directed environments throughout the twentieth century and how that is different from that which is only informally learned and often misguided in a conventional school setting. Now, I would like to take the opportunity for voices to be heard from individuals and families who have been impacted by this historic foundation as it unfolds in the early twenty first century. Let’s hear how their own foundations have spelled out a new understanding of sexuality and gender in the development of young people who do not necessarily fit the heteronormative accepted definition. I decided to start out by asking around at the SDE-aligned school my own children attend.

Mary, Gigi & Ash

Thirteen year old Ash goes to the Agile Learning Center (ALC) in New York City, where my two sons also go to school. Until I asked Ash for an interview, aside from the occasional nod of a head in the hallway, we only knew one another from a couple of times he joined in on a Theatre of the Oppressed class I volunteered to teach at the school last year. Mary and Gigi are Ash’s parents.

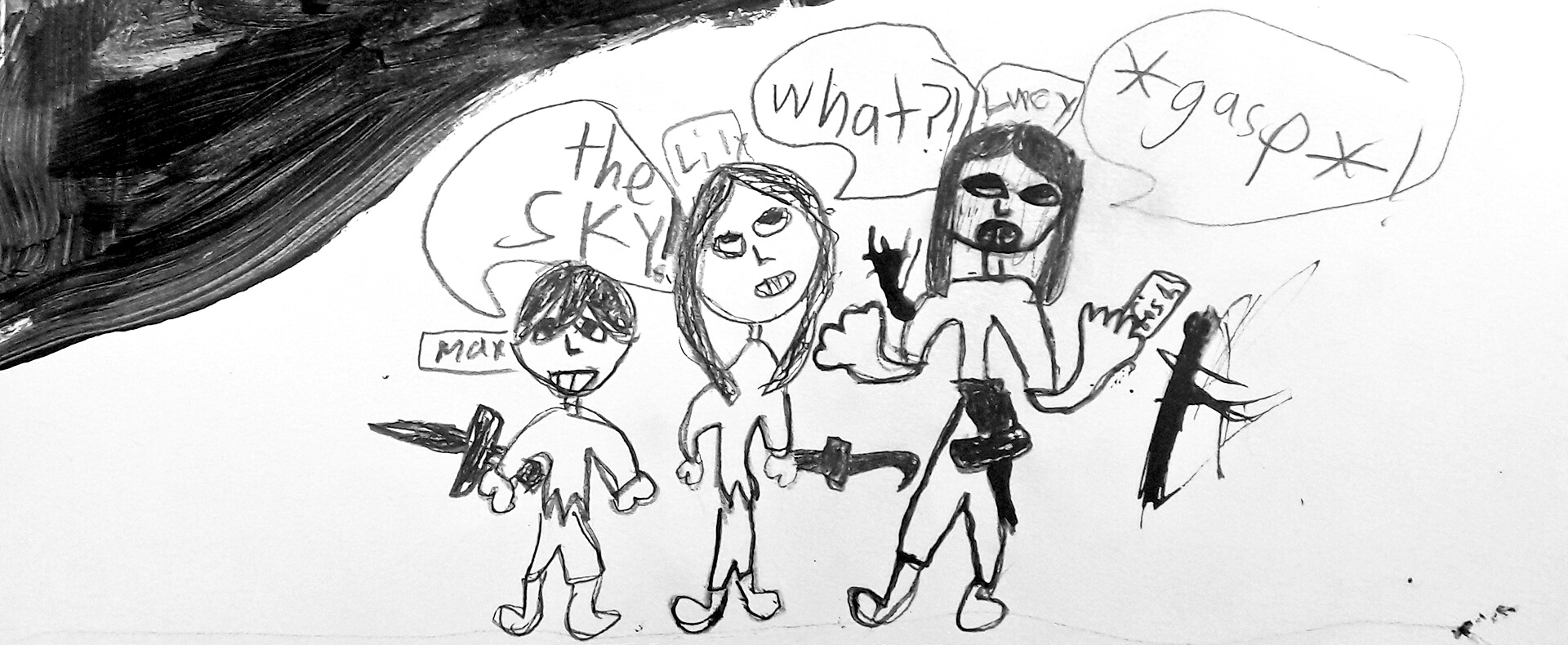

Ash describes himself as “a non-binary teen who draws in their free time and is generally part of the LGBTQ community.” When he was very young, he went to a Montessori school but has otherwise been at the Agile Learning Center for all of his education, dating back to when the school was originally the Manhattan Free School. Gigi describes herself as a cisgendered queer female who works in the mental health field. And Mary explains that she is a gender nonconforming stay-at-home parent and that she and Gigi are polyamorous, “so, we have other people that share our lives with us.” Both Mary and Gigi are LGBTQ U.S. Navy veterans.

Since Ash has been in a self-directed learning environment for almost all of his life, I was interested in finding out what that experience has been like for this family. I first asked Mary and Gigi why they chose an SDE-aligned school for Ash, to which Gigi decisively replied, “No homework and no exams. I hated that when I was a kid, and I didn’t want that for [Ash]... we were moving back to [New York] City and we needed a school for him. And we definitely did not want to put him in public school.” Ash added that, “self-directed schools [as compared to public schools] are more about respect and kindness and being a better person and being respectful to other people, especially minority groups.” Gigi then added:

The other thing I love about the free schools is that the parents come in and it’s very welcoming for the kids to even talk to other adults about pretty much anything... [including] what their family structures are [like] and the normality of gender fluidity and whatnot. It’s just a nice, refreshing, warm welcome — people coming together.

I have heard from many parents and students over the years that a big part of what has drawn them to Self-Directed Education environments in general has a lot to do with creating safe places as a community, and so, it seems natural that this would extend to one’s perception of their own sexuality and gender expression and that some families would seek that out.

When I asked them what they thought about childhood innocence and the question of how early is too early to introduce these concepts, Gigi thoughtfully replied:

I feel like it is important to slowly introduce certain concepts but also to let it come naturally without guarding children against it, as if there’s something evil. When they encounter someone who identifies as non-binary or as genderqueer, they’re going to have questions because that’s not their norm at the moment. Parents should take this initiative to then educate rather than say, “No-no-no-no, we’re not going to discuss that. You’re too young for that.” But obviously they’re not if they see it, they observe it, if they have questions. I think these questions should be answered and explored together as a family rather than just shutting it down.

So, I don’t like the phrase or the concept that children are innocent, and we need to keep them innocent. Because then that leads to children not feeling comfortable enough to come forward if something happens to them. We want them to come forward, but if they don’t have the words because no one taught them the words then how are they supposed to come forward?

Developing the language to talk about one’s sexuality and gender expression is crucial to one’s development as a whole being. And yet, it is a topic seldom listed in “the basics” of a school curriculum. And when sexual education classes are offered, the voice heard is often only the one point of view of the adult in the room. Rather, I suggest creating a space safe enough and to leave time big enough for all of the voices young and old to be encouraged. I suggest a space where all members of the community are listened to and respected so that the sound of diversity that truly makes up a community can come through.

When I asked if they had any last words, Ash responded, “Learn about your children before kicking them out... There are many LGBTQ+ children who are kicked out [of their homes] before they are eighteen due to who they are, which I think is a harmful thing that happens in our society and it should change.” Those are some wise words from a teenager: let’s all listen to, learn from, and respect our children for who they are.

Abby

Years ago, when I was starting to run a summer camp out of the Brooklyn Free School, and I was considering hiring some of the interns for summer camp staff positions, I asked the kids at the school, “Who would you want to spend your whole summer with?” Everyone I asked unanimously pointed me in the direction of Abby. Such an endorsement was good enough for me, and so, my interview with Abby lasted maybe five minutes. That was how we first met. A year later she was volunteering at the Agile Learning Center, the school Ash and my children now attend. Soon enough she became a facilitator and then the co-director.

I started our interview for this article by asking Abby about her own childhood, specifically with regard to her perception of sexuality and gender. In explaining her Catholic school upbringing, she remarked, “There were boys and there were girls and being radical was... expanding the possibilities for people playing the role of girl. Which at the time was my mom being so cool and hip that she encouraged me to roll in the dirt and climb trees and she bought me a carpenter set as a kid.” Abby continued to describe growing up in such an environment:

No one got a “no” or a “stop” except the adults. And there is an extent to which the boys were granted more freedom in ignoring the ‘nos’ and the ‘stops’ of the adults than the girls... It took being a teenager and not trusting my “no” and my “stop,” not valuing my comfort and safety enough to set and hold boundaries.... [I] was suffering as a result of that... [T]hat is the violence we do to children. Children don’t mistrust themselves in the world when they’re in healthy, nurturing, supportive, organic relationships.

It appears that in part, having her mother as a good role model, Abby was able to break away from the gender discrimination placed upon her as a child in her Catholic school upbringing, to recognize what was happening to her, and to stop the pattern from repeating.

When I asked Abby if she saw a link between the victims of the #MeToo movement and this “violence we do to children,” Abby responded, “Yes, but it’s more nuanced than that... we don’t always think about which roles we give power to or which people. Or the fact that we give power and that we don’t have to. But there are consequences—extreme ones—for refusing to give power in certain circumstances.”

I turned the conversation to the Agile Learning Center that Abby now runs and asked her how she perceives it to be different from conventional schooling and society with regard to children and power over one’s body and their own choices about their sexuality and gender expression. She answered:

We focus a lot on communicating with kids about them being in charge of their bodies, being responsible for their choices. It’s like, I’m not going to assume that I can give you a hug. I will ask and if you say “no,” it doesn’t mean we hate each other just, you know, you don’t want a hug right now and that’s okay. [The staff] model that with each other and with kids and help them find language to be practicing consent.

...The conversation is the culture. If we start with them while they’re young talking about different forms of relationships and different forms of love and different forms of expression, then they get over the place where they’re like “Is this normal or not?” and can get into the work of “What feels good to me?”

Imagine a learning environment where children have the space and the time to safely grow into beings with healthy, nonjudgmental attitudes about their own bodies; an understanding of consent and respect for one another’s bodies, spaces, and feelings; and the ability to communicate, honestly, how they are feeling. This is the culture that is being set and the culture through which the children at the Agile Learning Center in New York City are being raised.

Jenny and Chris

I met Jenny and Chris’s son Alf when he was four. He started in my son James’ class at the Brooklyn Free School a year after we had first enrolled there. I remember Alf wearing a sparkly dress the first time he and I met. He always had really glorious outfits on that were an amalgamation of styles, always somewhat effeminate. Then Alf attended the Agile Learning Center for a year. And now, many years later, Alf and I are together at Brooklyn Apple Academy, a self-directed homeschooling resource center Alf attends part-time and I joyously work at part-time. Alf and I have joked around that we might be the only two people who have tried out just about every Self-Directed Education environment there is to try in New York City. Now ten years old and unschooling, Alf comes in to Apple more commonly in camouflage pants and a Guns n’ Roses t-shirt, sometimes wearing aviator glasses and a baseball cap.

I knew that Jenny and Chris had in part chosen the Brooklyn Free School as a space where they thought Alf would be able to feel comfortable wearing dresses to school without being bullied. And so, I thought interviewing them would be perfect for this article. Starting there, Jenny explained:

Alf expressed an interest to wear dresses really naturally. Next to his daycare was an Old Navy, and he went in with us once and saw a dress that his friend—this girl, his little preschool friend—had, and he just wanted it. So we were like “Okay, cool!” ...[Alf] just picked it up as if it was no different than if he had picked up a t-shirt and jeans or whatever.

Jenny then explained how the teachers at his daycare began to make comments about what Alf was wearing, which began Jenny and Chris’ search for an alternative model of school where Alf could comfortably wear what he wanted without gender bias. This led their family to the Brooklyn Free School. Jenny continued:

One of the things I realized when we went to Brooklyn Free School is it was a little naive to think that there was a sort of utopia where kids wouldn’t think that that was weird... Kids live in this culture and even if they go to a [SDE-aligned] school for six hours a day, that doesn’t mean that the rest of their days and lives they’re not seeing and experiencing the culture that we live in that does constantly perpetuate these stereotypes of what all boys and girls should or shouldn’t wear... It was a wakeup call for me.

And although that first school that Jenny and Chris chose for Alf ultimately did not give Alf the unrestricted ability to wear clothes socially atypical for his gender role, they continued to reinforce at home that the choice was his to make, using language and attitudes that supported an open acceptance of whatever Alf chose to be. Jenny again:

When we talk about dating or getting married, we always talk about, “When you get older and you have a boyfriend or girlfriend...” or, “Do you think that you’ll ever have a wife or a husband when you’re older?” We always present both options. We never assume one option or the other.

Alf ultimately stopped wearing effeminate clothing during that first year at the Brooklyn Free School, and Jenny said that while “it was partially because of the feedback from classmates” it may have also “simply been that he grew out of it too.” She explains that, “even very liberal progressive sorts of families — especially heteronormative families — still prescribe — potentially unknowingly — to gendered choices for their children, whether they’re aware of it or not.”

And while I was interviewing Jenny and Chris, I decided to ask about one other unconventional aspect of their family: Chris is a stay-at-home dad unschooling Alf, and Jenny is the one who goes to work and provides financially for their family. Jenny explained that “it was just sort of the situation, I was just actually more career-minded and enjoying my career more than Chris.” But Jenny does “see it a little bit like an activist choice, and I am proud of it. As a feminist... I still feel a desire to sort of flip those roles.” And Chris explained his role in the family:

I remember growing up admiring my mother, I wanted to do what she did. She was home doing all the cool things like baking bread and cooking... I’m a homebody, and I always have been. And so it kind of felt comfortable to me... It was not an unnatural thing for me.

And so, using Abby’s words, Chris and Jenny’s family seem to have naturally transformed from “Is this normal?” to “What feels good to me?” And as Jenny explained about their family’s choices for Alf, “It’s not fair for other people to make a judgment call or decision, basically making a child’s world smaller by deciding for them what they can do or can play with, what they can wear or whatever. So to me it became a question of freedom of choice for my child.”

Eve

I met Eve’s husband Gavin in 2005 when the tech company I was working for hired him as a project manager. Gavin and I then worked at two more tech companies together over the next two years. Coincidentally, years later we both moved into the same neighborhood in Brooklyn and had children close in age. It was at my son’s birthday party one summer that Eve and I struck up conversation about how there needs to be a junk playground in New York City. We committed to meet once a week until one was opened, and after roughly three years of mostly volunteering our time, we had opened play:groundNYC.

Gavin and Eve’s son Zayne is mainly unschooled but also goes to Brooklyn Apple Academy part of the time. And similar to Alf, at a young age Zayne started wearing clothing customarily found in the the girls section of clothing stores. I caught up with Eve to follow up with her a bit on her parenting choices with regard to Zayne’s education and his desire to dress in girls’ clothes, mainly fairy costumes. Eve tells the story:

From a very young age Zayne was very gender fluid in his choices, the toys he chose, the colors he liked—he liked pink and purple for a really long time—but he also liked trains and trucks... He got really into the Tinker Bell series of movies and really liked the kind of strong, cool style characters. He would dress as Zarina the pirate fairy a lot.... and he would borrow [his sister’s] clothes a lot, and he would say he wanted to wear this to school. And I was like, “We’re not in a normal public school, so you can wear whatever you want as long as you can move around and do what you need to do within the space where you are.”

Zayne started at Brooklyn Apple Academy at five and began using rolls of silk fabric he found there to create dresses for himself. He was thoughtfully asked by Noah, the founder of Apple, which gender pronouns he preferred to use. And as Eve explained:

Zayne said very definitely: “she.” And Zayne looks the way Zayne does, he could look like either a boy or a girl, and everyone else at Apple started calling Zayne by “her” ...and then eight months later or so he stopped wearing the dresses and really went full on wearing the sort of clothes of a gender normative boy. But there were still friends of his from the early days at Apple that still referred to Zayne as “she,” and that never bothered him. And Apple was totally fine with supporting the fluidity.

...Kids really need that fluidity when they are young to try and identify their tribe. And Apple really provided the space for that... Zayne could be he, she, they. There was no judgment.

I spoke to Eve about the Michael Ian Black interview mentioned in Part One of this story, on Black’s perception that “boys are broken.” In knowing Zayne well, I am familiar with his often rough and tumble attitude at Apple, and I wanted to get Eve’s take on masculinity and forcefulness and to hear her perspective as a mom of a strong-willed boy who also has identified as being gender fluid, as to what she thought about Black’s theory. Eve replied:

I have had conversations with other moms of boys. We have strong girls, and girls can be feminine, and girls can be proud of their bodies, and women can dress sexy, and they can be strong, and they can be outspoken or they can be shy and quiet. Those are all acceptable...

I think we need more complex versions of boys that are represented in pop culture references and that are allowed in the culture and within school environments. When you look at reports about autism and ADHD, the boy to girl ratio is like four boys to one girl, all being diagnosed with behavioral disorders.

Everybody loves the boy that’s so sweet and sensitive. What is wrong with that boy that’s strong? How do we find space for these boys to be proud of what they bring to our culture and what they become? And as a mom of a boy who is very strong and strong-willed and termed “excitable” and all these other terms that are a negative association, how do I celebrate who he is as a kid when the rest of society wants him to stop doing what he is doing?

Zayne paints for us a very special image of a child, who fits into both a place where he has enjoyed dressing in the fashion of fairies and identified with feminine pronouns and yet is also identified as a determined masculine individual. A young person like this has every right to have a space to develop in, to find himself and to find safe ways to express himself, just like any other child. But with a scarcity of such spaces, perhaps boyhood is in fact “breaking.”

Mel

Mel and I met about a year and a half ago when she started as a facilitator at the Agile Learning Center. Over that period of time, she has become an increasingly more important part of my family, as her relationship with my two children who attend ALC has increasingly developed. I invited her over for dinner the other night and we chatted about her experiences as a genderqueer lesbian who is also a facilitator in a Self-Directed Education learning center and what that means for her role there.

Mel explained a bit about her own process of coming out, which for her started in adolescence:

I remember in middle school in the locker room at gym class being called a lesbian and knowing that it was an insult and not knowing what a lesbian was... I wound up just doing the regular high school things. I was a theatre nerd as all closeted queer kids are [laughter]... I read a lot, and I was very into storytelling in general. I was in plays... and so I was surrounded by all these stories about how romance looked and should be. And so I was like, “Oh, I’ll just go get me a boyfriend.”

I would break up with one and then go find the next. And I could never quite articulate why I was always breaking up with them and why it wasn’t feeling the way that it looked in the television shows. But I knew that that was the thing that you did so, you know, I had boyfriends.

For college, Mel went to the Gallatin School of Individualized Study at NYU, where she met Abby. There she studied politics and education and soon discovered the world of Self-Directed Education and, in particular, the philosophy of free schools. She wrote her senior thesis, which at NYU is called a colloquium, on “how to have a democratic writing classroom.” After college, Mel broke up with her longtime boyfriend and, as she explained, “I remember sitting up in bed and being like, ‘Maybe I’m gay,’ and then dismissing it actually out of hand. I was like, ‘Well people just know. And I don’t know, so I must not be like that.'” She continued, “Eventually I figured it out. And I did come out.” She then struggled with her existing friendships as people close to her questioned her new identity:

The uncertainty that I had internalized was reflected at me by the world when I came out... Even now, when you see queerness celebrated, it’s mostly white men who, like, are also gay. It’s a Will and Grace model of acceptance, which doesn’t leave a lot of space for really femme lesbians or genderqueer people.

Soon enough, Mel became reacquainted with Abby at a time when Agile was looking to add an additional facilitator onto the staff, and it was a perfect match. When Mel started at Agile, she explains:

I felt I had a responsibility to be really visibly gay... as a facilitator in a self-directed environment.... It’s really important because a lot of our job is modeling that there are different ways of being, different adults do different things. And I do other things: I read a lot of books, and I also go climbing, and I do acro[batics]. It’s one thing on a list of things about me. But it’s a really important part about me. I’m gay, and I wanted to be able to be the person that I didn’t have when I was a kid and be just out and excited about it and happy to talk to anyone about it and not be ashamed.

In addition to sexuality, Mel also had some fascinating observations to make about gender and childhood:

I find that kids of all ages are much more interested in talking about gender than sexuality because it applies to their life. Talk to any kid and they know that there’s boy stuff and girl stuff. And a lot of them know that it’s not fair, they feel a sense of injustice about the way the world is split into boy and girl stuff.

It’s wonderful how children intuitively pick up on injustices in the world and, when given the opportunity to do so, freely express themselves and act upon it. I have seen this time and again in my own work with young people in Self-Directed Education environments. It was nice to hear that Mel has experienced this with children as well — that she has provided the young people she works with a platform for normalizing many views of sexuality and gender and given them the opportunity to comfortably discuss these topics as they arise.

Conclusion

In no way were these articles intended to cover all of the issues related to sexuality and gender in childhood. Rather, it was meant to introduce the history and provide a sampling of real people’s stories in today’s Self-Directed Education environments. This is an important topic that is not often enough openly discussed due to sensitivity and puritanical societal norms. I hope that these articles have stirred the pot a bit and helped people from many diverse backgrounds to continue the conversation. I will leave you with this last bit from my interview with Mel:

A kid came up to me recently, an 8 year old girl, and just handed me a note. I opened it up and there was a caricature of me as a unicorn with a rainbow mane and it just says “Stay pawesome Mel, Mel is gay, that’s ok.” ... It’s really interesting how they’ve internalized it as like, “Oh yeah that’s one of Mel’s superpowers, like she knows every book in the library and she’s gay and her hair is blue.” You know, those are the things that they care about.

If you enjoyed this article and feel called to give back to ASDE, here are ways you can support our work:

- Donate money

- Share our content with others! Click one of the buttons above to easily share on Twitter, Facebook, or email.

- Consider becoming a Contributor for Tipping Points

Tipping Points Magazine amplifies the diverse voices within the Self-Directed Education movement. The views expressed in our content belong solely to the author(s). The Alliance for Self-Directed Education disclaims responsibility for any interpretation or application of the information provided. Engage in dialogue by reaching out to the author(s) directly.