Introduction

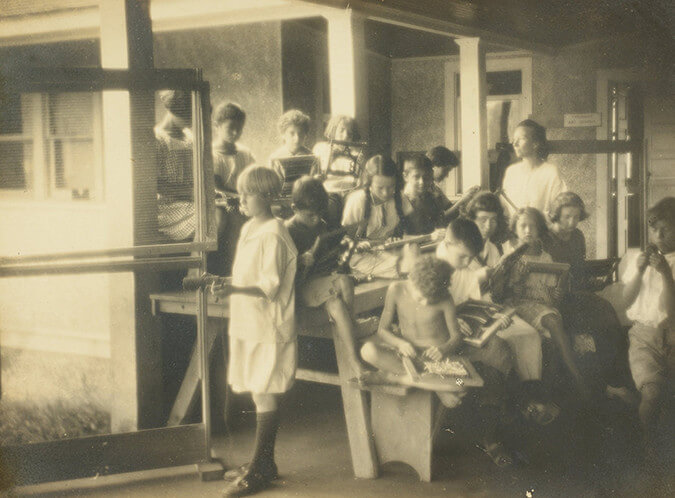

The self-directed anarchistic Stelton Modern School ran for over four decades and was the most influential and longest lasting school of the early Twentieth Century Modern Schools (see my previous article for more on the history of the Modern Schools). The Friends of the Modern School organization has run since 1973, serving both as a historical reference of the Modern Schools as well as an advocate for current models of anarchistic education.

At the annual Board meeting on May 19, 2018, I had the opportunity to sit down at the historic Goldman House for an interview with two former students, Leo Goldman and Jon Thoreau Scott. Now in their mid-eighties, the two best friends reminisced over their years at Stelton and the impact the school and community had on their lives. Below are excerpts from our conversation, a rare insight into the inner workings of the historic school.

Leo Goldman was born in the Goldman House, which was built by his communist father Sam Goldman in 1915. He attended Stelton from the age of two until eight. He remained in central New Jersey for much of his life, working as a mechanic for Johnson & Johnson and AT&T. He retired to New Hampshire where he now lives with his wife.

Jon Thoreau Scott was born in East Taghkanic, NY in 1932 of self-proclaimed Thoreauvian anarchists, John and JoAnn Scott. His parents were teachers at Ferrer Modern Schools (Stelton and Mohegan) for many years. Jon was commissioned as a second lieutenant after which he became a USAF pilot flying C-47s. He obtained a PhD in Meteorology from the University of Wisconsin and later joined the faculty of the Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, retiring as Department Chair. Jon lives with his wife Kathleen on a 32 Acre “minifarm” in Altamont NY and published a book on plate tectonics (see his website tectonicforces.org). Jon was the Secretary of the Friends of the Modern School from 1992 to 2018 and Treasurer for much of that time.

The Interview

Alexander Khost: And so were there any sorts of regular activities or classes or...?

Jon Scott: You had to be there at nine o’clock for a morning assembly. And you had to be there at three o’clock to clean the room that you were assigned to clean.

AK: And what would morning assembly look like? Like, what would you do?

JS: Well, we sang songs, we danced around. And-

Leo Goldman: Look here in the garden, something beautiful is growing, shaped like a cup of yellow, what were... daffodils, or I forgot... opened to the sun. A few years ago, Sally Brown was here and we were singing that.

JS: [sing-song] Pretty little dandelion, growing in the grass [laughs].

LG: And what was the one with, I can never get the words to “let’s hang General Franco from the sour apple tree?“

JS: Oh yeah, [singing]

LG: During the Spanish-

JS: “Let’s hang General Franco from the sour apple tree! Hang General Franco in the sour apple tree...“

LG: I tried-, needless to say, anti-Franco in this town. I tried to find the words to it, you know, that’s the only part I knew and Google doesn’t know them yet! [laughs]

AK: Wow.

[...]

AK: Well, first of all, how many years were you both...?

LG: Well, I was there full time until I was eight. I guess I started two or three, I don’t remember how old I was.

JS: I started at two and ended at fourteen.

AK: And then where did you guys-, did you end up going to some sort of a public school?

LG: We moved, my family moved North, so I went to a high school up North.

AK: And you?

JS: And I was there until I came home with singed eyebrows and everything else because they decided to burn me at the stake [laughs]. And it wasn’t that, the fire was far away, but they were acting something out and then somebody kicked the fire too close to me. And it came up and singed my eyebrows.

AK: Oh, so your parents took you out at that point?

JS: No, I just singed my eyebrows a little bit. They kicked the fire close to me.

AK: Uh-huh.

[CROSS TALK]

JS: Alex, are you more interested in the school or the community?

AK: I’m kinda interested in both. I mean, at least in my mind, they’re sort of...

JS: Okay, let’s go back to what do you do after the morning assembly.

AK: Yeah.

JS: Mostly, we played or we had a project—woodshop, printing, weaving room, art. And you did what you wanted to do. If you wanted to learn how to read, you went to the reading teacher, who was my mother. And she started you out reading. And after I learned how to read, I came to the morning assembly, and went home and read books all day. That’s the way to read. That’s the way to learn how to read. I wanted to learn the comic books, because he had tons of comic books. And Mike Rappaport had tons of comic books.

LG: I couldn’t read ’em. Helen Schneider or Helen Tooley, or whatever name she went by, she would always read.

JS: She would come for what, two hours or an hour?

LG: In the morning, I think.

JS: Probably ten to eleven or something like that. And she would read stories to us. And when I learned how to read, it was poem called “Robin Redbreast.” You familiar with that?

AK: I’ve heard of it, yeah.

JS: Yeah, and my mother knew I knew the words to that song. So she said, read this poem. And I said, I can’t read. Well, look at it, see... and then I started reading a little Robin Redbreast. I used to know the whole thing [laughs]. But so, it couldn’t have been more than two weeks. At age nine and a half, I learned how to read. And that’s all it takes, when you want to do it.

AK: Right.

JS: Then I decided I wanted to read The Wizard of Oz.

LG: Wasn’t there somebody who wrote that a kid really isn’t ready to read until they’re eight or nine because their eyes aren’t fully developed at that point.

JS: Yeah!

LG: And I was eight, I guess before I could learn. In fact, they started me in school because of my age, in the third grade. And the first thing we had to do was the Pledge of Allegiance. What the hell is this? So, I just followed the other kids. And I noticed when you pledge allegiance, you put a hand out. It was 1941, September. Which after December, they decided it looked too much like this [gestures]. So, they said, just keep your hand on your heart. You didn’t have to extend your right arm anymore.

AK: Huh!

LG: But I went there, and in those days, they’re reading from the Bible. To me, it was a Holy Bible [mispronouncing]. What are they reading? I had no idea. I had never seen a Bible in my life. And then they had to recite the... they always did the 23rd Psalm, with the one line, “he anointest my head, my cup runneth over.” Okay, the Yiddish word for head is “kopf.” And my father worked for a painter who had a picture of a paint, it covered the earth, it was a picture of a globe with eyes and all, and paint running over. Okay, he anointest my head with oil, he’s putting oil on my head and my kopf runneth over. [laughs] And I probably was in high school before I realized what they were really saying! That was my exposure to organized religion, I guess.

JS: The community was a wonderful place.

AK: How big was the community when you were there?

JS: It was from here to Stelton Road and then as Leo says-

LG: Vintner’s Lane, Brookside Avenue.

JS: Yeah.

AK: I’m sorry, I mean, like how many families would you say, you know, give or take?

LG: A hundred? Two hundred?

JS: I honestly think there were three hundred.

LG: We’ll put it this way: in those days, the population of Piscataway was like two thousand. Now it’s sixty. So, huh. It’s-. [CROSS TALK]

JS: Probably close to a hundred houses. But they weren’t all associated with the school.

LG: A good number of ’em were.

AK: Oh, so there were some people that were in the community whose children didn’t go to the school.

JS: Or didn’t have children, they were older. And that’s probably one of the reasons the school died, is that people with children, the children grew up and went somewhere else. And so there were no more children. And that’s one undesirable feature of a community to be built around a school. It’s like the Shakers.

AK: Right.

JS: There’s no reproduction so they have to be volunteer. And so that’s... But I think it was Camp Kilmer, more than that.

LG: Yeah.

JS: That did it. But it was both.

AK: And your father taught at the school too, didn’t he?

JS: He taught early on. He taught, he gave nature walks. But he started a newspaper called “Money.” He was interested in social credit. I don’t know if you know what that is.

AK: Not really.

JS: Social credit system is to balance the ups and downs of the economy. So when the economy is high, the government pays people. And the other way around, you pay the government. It’s to prevent depressions and booms and busts. And that was his. He would go to New York for three days and come here for four. He was probably the best gardener in the area. And we sold strawberries and blueberries.

[...]

JS: No doors were locked. We just had a screen door hook. After Camp Kilmer. That’s how we locked the door. Just... But uh...

LG: But after the morning assembly, you could go anywhere you wanted to. So we would go Lake Nelson and swim, or skate in the wintertime. I skated or sled-rided. Sled-rode to school from my house, which was on the stream.

JS: Played kick the can.

LG: Yeah, kick the can was one of our great games. And kickball. And dodgeball. We played dodgeball, which came back. We used to play that way back when. Hide and go seek. Or kick the can. Hide and go seek and kick the can were the same thing. And hand-me-over. Remember that? Hand me over, let it come?

JS: Vaguely.

LG: There was a shop and-

JS: Oh, throwing the ball over the-

LG: Throw the ball over the roof and you have to catch it. If you catch it, you could go to the other side and hit somebody with it. And they’re never on your side until one team was wiped out.

AK: Oh wow.

LG: It was a game that we made up. It was made up at the school somewhere.

JS: You’d just throw a tennis ball over a pitched roof. And you had to catch it though. And it had to hit the roof, you couldn’t throw it over.

LG: Yeah.

JS: Had to go-

LG: Had to go down.

AK: Oh gotcha, gotcha.

LG: Yeah, so I don’t remember what happened if it hit the ground first, you just had to do it again, right?

JS: You had to be honest.

LG: Ha!

JS: You had to [CROSS TALK] the other team, on your team, then I guess...

LG: That was-, we spent a lot of time playing that game.

JS: A lot of hiking. We would hike to New Brunswick. We’d hike to the Washington Park. The monument of the...

LG: There were no trees. And when you look here now, you could probably see half of school looking down. I think mostly the old trees have gone now. But it was quite flat. You know, this might be one of those trees, where we had a [INAUDIBLE], remember we had cows? And pastures between here and all the way pass Votec. But when they built the cap, we lost our pasture land, so she had to sell the cows. And that-

JS: Now, Alexis Ferm, Uncle, in my opinion, was the person who knew best how to operate a freedom in education... He did not teach. Except you know, you have to clean up. You have to put the tools away and stuff like that. But he never taught anything.

I needed to-, Dougie and the kids were coming up the street doing their arithmetic. You know, multiplication tables. And I asked what they were doing. They were younger than me. And they said, we’re doing multiplication. I said, what’s that? And they laughed at me. So I went to Uncle and I said, I want to learn the multiplication table. I wanted to learn how to multiply. And he gave me the book. The composition book with the twelve by twelve on the back and he says, memorize that. And so after three hours, I couldn’t memorize that. He showed me a shortcut. Do the easy ones and either subtract or add from the easy ones. So, the fives and the tens were easy. So seven times ten is seventy, minus seven is 63, so that’s nine times ten. And you could go the other way. And I got ’em all. And he checked me and he said, well, now you know how to multiply. So, I went out to the kids and asked ’em the hard ones. You know? And they couldn’t do the hard ones. You know, nine times seven is for some reason, a rather hard one. And I would get it right and I would laugh at them. Cause they couldn’t get it right. In four hours...! Four hours!

We did the whole algebra book in four months. August through November. And with just doing the problems in the book. And so I learned how to do algebra in four months. And went to high school and they made me take algebra, cause I started in the ninth grade. And I said, well I already took the algebra. They said, no, you gotta do it. It’s the rules. So I went to the algebra class and, needless to say, I got a hundred on every two weeks, or every week, they’d have a quiz. And I’d get ’em all right. And the teacher mentioned it and the kids laughed at me. He got ’em all right, you know. So after that I’d get one wrong.

AK: [laughs]

JS: So then, I asked the teacher, his name was George Robinson, I said, is there any way I could go into geometry instead of taking algebra? He said, well, we’ll try. He went to the principal, and the principal said, “no, he’s gotta take algebra.” What for? I knew it already. There was only one thing that was hard, it was the quadratic equation. And you had to learn that formula. You know? Which is a + or -...

LG: [INAUDIBLE]

AK: I knew that for a week of my life.

JS: That was about the only thing that was a little bit different from what I had taken at the Modern School. The Modern School, like Sudbury, you can learn. And it’s much better to do it by yourself than to be taught. Because especially if there’s competition. That’s what I didn’t like about high school or schools, American education. It’s the competition that causes people to be bullies, in my opinion.

LG: Gotta show up on the top of that bell curve, right?

JS: Yeah. You gotta... forced competition-. Competition is bad enough without being forced.

AK: Do you feel like that leads at all, you were talking about racism and prejudice and that sort of a thing? Do you feel like that sort of competition and the trying to be the person on top, or anything within the conventional schooling system, also like the idea of how public schooling sort of ends up, whether intentionally or unintentionally segregating a lot?

JS: I think that’s what it does.

AK: And you feel like being in the community at Stelton-

JS: There was no competition except in sports, of course. And even then, we didn’t care who won.

LG: Because the ones you were playing against today are on your team tomorrow. [INAUDIBLE]

JS: We took the bat and we went...

LG: I got Joe, you got Bill... [laughs]

JS: We invented games like playing baseball with three people on the side and...

[...]

LG: Both of us are only exposed for the Ferms. The Ferms never had any classes whatsoever.

AK: Mostly Uncle [Alexis Ferm], right? Cause he-

LG: You’d talk with Uncle.

JS: And Uncle was by far the best.

JS: You learned never to put a wood plane down with the plate facing down. It always had to be the side or you got kicked in the rear end.

JS: And you know, put the tools away and you gotta clean up. So, those things, you had to do.

AK: But that’s a respect for materials, rather than a-

JS: Yeah, and that was-

AK: But if you didn’t want to use a plane, you didn’t have to.

LG: No, no.

JS: He didn’t tell you how to-, but he did say you gotta put it on the side, I remember that. [laughs] Because it gets dull.

AK: Yeah.

LG: I still had that habit of [CROSS TALK] you’re gonna get kicked in the pants.

JS: He would tell you how to use a tool.

LG: Yeah.

AK: Now, would it just be sort of your natural—you’d be interested, you’d walk in...?

LG: The shop was separate. They had the print shop in a little classroom on the side and then the woodshop. I think they had a metal shop at one time, didn’t they, before our time?

JS: They had a metal shop and they also had a ceramic oven. When I was there that had busted.

LG: And the side rooms, they kept wood in it.

JS: Yeah, and the print shop was very busy. It was a [CROSS TALK] place.

LG: I always remember, we all learned how to set type-

JS: Yeah.

LG: -run that press. And Uncle, of course, he would hook it up to, there was an electric motor up in the attic, with a belt. And he would do it under power. But we had to do it with the foot pedal, cause we had this single letter press and a big fly wheel on it. And then the release that if you knew you were gonna get your hand caught in the plate, you stepped on that thing and the plate wouldn’t close all the way. We were seven, eight years old. We were running this machine.

And plus in the main building was the weaving shop. We did weaving and things. But I don’t know how many different type fonts they had there.

JS: How many different what?

LG: How many different type fonts. Because remember, they had two rows and each one was like, a chicken coop, you know? There was type-[CROSS TALK]

AK: They had the California case trays, like the-

LG: The ones you buy in antique shops.

AK: Yeah.

LG: And each one was a different font. And there must have been, I’d say twenty-four different ones.

JS: Oh god, that I don’t remember.

LG: They had two rows of type, and they were all like-

AK: Oh, I see, they were up like this!

LG: You sat on one side or the other.

JS: I remember the E was the biggest one. [laughs]

LG: And they had the little linoleum.

JS: Those were bigger.

LG: And the linoleum press with the wheel on it. And then on the left was-

JS: But you could do anything you wanted to. And you didn’t get any official instructions, except you know, you have to clean up and certain things that you don’t do with a tool, for example. Like, don’t put the...

AK: What about things like the Voice of the Children? Would that be an adult sort of suggesting it?

LG: No, that wasn’t around when we were there, was it?

JS: Oh yeah, I wrote a little poem for the Voice of the Children.

AK: Did you?

JS: Yeah, yeah.

LG: I never did.

JS: It was three lines, I think. Maybe two. [laughs] And when they dictated it to Teesa Winnecore [ph] and she wrote it down.

AK: Was this an older kid or an adult?

JS: She was about four years older.

AK: Okay.

JS: Than I. And I set the type. And I ran the machine. Not for just mine, but for...

AK: Multiple copies.

JS: What we did mostly when the students operated the machine, we printed throwaways. Which were advertisements for what was going to go on, on a Saturday. A dinner, or a speech, or a play, or something like that. Somebody was assigned to hand ’em out on the first tract, which was from the bridge to the highway. The second tract was from here. And then the third tract, which was Poplar Grove Road and Water Street. And then we named the other one Brookside Avenue.

[...]

AK: How do you feel like that influenced your own parenting?

JS: Well, I wanted my daughter to go to the Free School in Albany. It was very difficult. We lived out in the country. It was about fifteen miles, maybe a little more, to get to the Free School. So, it was really difficult to do that. And that was the only freedom of education school in Albany.

AK: Roughly when was this?

JS: Uh...

AK: Must have been...

JS: In the mid to late seventies.

AK: Okay.

JS: So, she had to go to the local public school. And my wife believes in public education. She was a teacher and she was a professor of education at the College of St. Rose in Albany. So we had a difference of opinion. And it was just no way we could get her to the school. But my daughter hated the school, which is not uncommon. I mean, read Peanuts if you want to find out about schools. And what schools do. You know, the kids hate the schools. It’s because of the competition. Mainly, in my opinion. And that’s what leads to bullying. That’s why we have a president who’s a bully. He’s been bullying all his life. He never gave it up.

AK: Was there any ways outside of school that you felt you were doing things different as being parents with your kids?

JS: I would say so, yeah.

AK: Yeah?

[...]

LG: But at the Living House, which was on Water Street on the corner there. They had a big pine tree, and on Sundays at seven o’clock, we would climb to the top because we could see the parachute from the airport. The guy would-

JS: Which is a big shopping center right now.

LG: Two motels there. But anyway, the guy would jump out of a plane with a parachute, that is. And it was a big thing, that was before the war, you know? And he’d drive by and I guess we were supposed to throw some money in the hate. I don’t know.

JS: And we did plays.

LG: Oh yeah. As You Like It.

JS: We did As You Like It. I was Touchstone. And what was your name?

LG: William.

JS: Yeah. Yeah.

LG: Also off stage-

JS: I got to stab him with a... [laughs]

AK: [laughs]

LG: Yeah, we were both suitors for the same girl. [INAUDIBLE] Audrey.

JS: Right. Yeah, it was quite a...

AK: How would you organize the play? Like, how would you figure out who was playing what part?

JS: My mother was the director.

LG: But we would do our own plays too. We would make ’em up. And on Saturday night, big crowd there, and we’d do our little play, you know. But it was usually from a storybook. You know, from one of the books, those stories that Helen would read. It was usually that. But some of the girls were pretty imaginative.

JS: They had a pretty decent auditorium there.

LG: Yeah. It was like, seventy? Inside we had benches. Little benches. And I remember the stage end, Jeff’s mother painted a big dragon on it. Of course, we learned-

JS: The stage was about this much off of the-. They had a curtain that you drew and there was curtains and there was lights. The lights weren’t too fancy, they were okay.

[...]

AK: I have two other questions in my head. One is, how much do you feel that politics, specifically anarchism played in the community? Was it something that was conscious that people were talking about? Was it a majority of the people?

LG: I think after 1917, communism became the dominant theme and his parents became communists. My parents stayed anarchists.

AK: Which seems like that was pretty common of the day, right? There were a lot of communists and anarchists?

LG: Yeah, but there weren’t that many communists. It was your father and mother and uh... Saul Kenner?

JS: Kenner, yeah.

AK: But this was something that was spoken about?

LG: There was a lot of argument, because I think it was Saul Kenner, who wanted proselytization in the schools for communism or socialism. And the anarchists would not buy that. So, there were lots of fights. And there were lots of fights about how free the school should be.

AK: Do you feel like the politics of anarchism were pushed in the school?

JS: I think not to the students. I didn’t even know what an anarchist was until way after I got out of college.

AK: Interesting, okay.

LG: The philosophy itself, you know, kids were always allowed to be themselves. I don’t know how it was after we left when it became primarily a daycare center. But there were very few students at that time. Gladys Horrowitz claimed she was mainly subsidizing it at that point.

AK: Were the Ferms-

JS: The Ferms. Well, Auntie [Elizabeth Byrne Ferm] died, ’43, quite a while before.

LG: Quite a bit before the school closed.

AK: Right.

JS: And my parents left. My father was very much against the communists. He started out as a socialist. Back in Missouri. But he hated communism. And he became more and more conservative. And he became a little prejudiced, according to what I understand. He was never prejudiced as far as I’m concerned. But especially against anybody who was Jewish. And he hated Sam Goldman, his father. And he hated Saul Tanner. And spoke out against him.

AK: But you were friends.

LG: Yeah, we were great friends.

JS: Oh, we didn’t care who [laughs]-. We were best friends.

LG: In fact, when I finished the eighth grade, I went up to his house and I was there two or three weeks.

JS: Yeah.

LG: I don’t think politics ever entered the talk. Busy picking blueberries. Pretty blueberries. So, the children didn’t-. My mother, she would never let me use the word Jew, for some reason or other, that was derogatory at the time. It isn’t anymore. I don’t know why. It is to me, and I never use the word, because of my mother. She said, don’t you ever use that word. And any other slang words against either blacks, Jewish, or otherwise. She was very vehement about it.

JS: You remember when Helen would do that “eenie, weenie, miney, moe,” it was always catch Scotty by the toe. And somebody came and said, oh, it isn’t it supposed to be the N-word?

LG: Yeah, catch a nigger by the toe.

JS: Yeah. And Helen, as much as she could explode, I don’t remember how it was settled, but we learned never to use that word again. And-

[...]

JS: The Modern School was a precursor of the schools in the sixties. I don’t know if you know Goodman. He knew about the Modern Schools and he was familiar with the Ferms and Auntie’s book, which is a great book.

AK: I have that, yeah.

JS: Even though, she was nowhere near as good as Alexis, in terms of how to apply it. How to apply freedom. She was brought up a Catholic. And-

AK: The little bit that I’ve read, that comes across.

JS: And there were certain things that she said that you gotta do. And Uncle was never that way.

LG: One lasting monument to her is my nickname. Which, now they call me Dougie, but when I was two, three, four, however, I used to bite. So she said, well, we’ll call you Doggie. And the kids changed it to Dougie. But nobody can figure out how Leo became Dougie, you know. [laughs]

AK: That’s funny. But just going back to the anti-racism for a minute. This is back early on, do you think it’s just because of the philosophy of anarchism or what do you think brought that about as far as a whole community of predominantly white people, right?

LG: Yes.

JS: It was only one African American family and he was not on the school side. The Mosleys were on the other side.

LG: The Banks’s were there.

JS: Yeah, they lived on Brookside Avenue. And then the Hankersons, which lived on [INAUDIBLE]-

[...]

AK: Yeah, I just wanted to finish up just as far as what you think it was as far as racism. I mean, if this was that early on, that’s kind of quite remarkable.

JS: Families were oh, fifty to seventy percent Jewish, I would say.

LG: A couple of Italians.

JS: A few Italians. And the Ferms and Jim Dicks was Jewish.

LG: His mother was Jewish. But his father was not.

AK: You didn’t know the Dicks at all, did you?

JS: Oh yeah.

AK: Oh, you did! Okay, I thought that they were at Mohegan, weren’t they? Didn’t they-

LG: [INAUDIBLE] lived to be what, a hundred and four? Her sister was Dora Rosen, who lived to be a hundred and... over a hundred. And young Jim Dick was there. He used to come to the meetings.

JS: I knew them very well.

AK: Oh, you did, okay.

JS: She died, she was what, over a hundred? A hundred?

LG: Who’s that, Nellie?

JS: Nellie. A hundred and four.

LG: A hundred and four.

JS: And after she died, Jim, Little Jim, was still alive. I stayed at their house once, when they had a hundredth birthday, I think it was for Nellie. But they were closer to Ferrer, in my opinion. I don’t really know that much about it. Than the Ferms. The Ferms were total freedom. The Ferms and Sudbury, probably, are pretty close. But the Dicks would have reading classes in the morning and different things like that.

[...]

AK: So, Ferrer you said, had required academic classes in the morning.

JS: Yeah. I don’t think they taught. They did a lot like the Dicks. Kids would read. And they would do experiments in science. And a lot of walking, hiking, you know, in the woods, and fields, and forests.

LG: I think the only prejudices I heard are when they were talking about various people and they’d mention Anna Winnecker, “boy, she’s such an anarchist.” [laughs] She never wavered, I guess, from anarchism.

JS: She was a strict anarchist. She’s buried in Waldheim in Chicago with-

AK: Emma Goldman’s there.

LG: Stanley Rosen is gonna be buried there also at Haymarket Square or whatever they call it.

AK: Yeah.

LG: In Chicago, I forgot the name of the cemetery. But I remember my father saying that there are so many people in this neighborhood named Lenny. Leonard. That it would have been inopportune for them to be named Lenin, so they were called Leonard. You had Big Lenny, Little Lenny, Little Little Lenny. Lots of Leonards in town. [INAUDIBLE] Lenny Zacaroff.

JS: Yeah.

[...]

JS: My father, even though this family probably were either socialists or communists would get swarms of bees in their house. And my father, they had a huge ladder and I’d climb up the ladder with a souper, I don’t know if you know what a souper is.

AK: No.

JS: It’s a section of a beehive.

AK: Oh, okay.

JS: And I’d climb up there and bang on the wall. And hold the thing with one hand and bang the other on a ladder about thirty feet high. And the bees would come out. They’d go in there, cause there were combs in there, and it was a little bit of honey. And so, we’d catch ’em that way. I remember doing two or three at that one house. The bees went always to the same place.

AK: And then you kept the...?

JS: We kept the bees. Yeah. Yeah, we had around thirty hives of bees.

AK: Wow!

JS: We sold a lot of honey. That was one of the things we sold. Strawberries, honey, blueberries, vegetables. And the nice thing about the community was that little brook. It doesn’t look like much now, but it was much nicer then. There weren’t as many trees. And I learned how to do a lot of things in the brook. That was a teacher. That was a fantastic place to learn things like fishing. Suckers there, and we’d try to sell ’em for five cents a fish. So, it was a great place to grow up. And not being forced to do things is a big advantage. When I got to high school, I was the hell ahead of my compatriots. They were, particularly in science and math. Which I liked, I wasn’t too fond of ’em. I won a history award. I won the science award and the math award. Every year, they’d have the best student in that particular area. And I won those three. I never won it in English. That still haunts me [laughs]. Leonard Ricault, who was a professor at the University of Pennsylvania for many years, he may have been Trump’s professors. Trump went to University of Pennsylvania.

AK: He went to Wharton.

JS: He taught at the Wharton School, as matter of fact. And he says that the way the Modern School worked hurt him. And he said, he got his PhD, he got his master’s-. He got his undergraduate at Rutgers, his masters at Illinois, and his PhD at MIT. Now MIT is pretty mathematical, in my opinion and Lenny said the Modern School not teaching me arithmetic in the beginning hurt me. I said, how can that do it? You can learn arithmetic in a day and a half! You know, he said, no... I think he just had this natural math fear. You know, a lot of people have. And he blamed it on the school. No way. If you read in Lenny Ricault, he mentions it.

LG: Vic Bass also felt like that.

JS: Yeah, Vic Bass said it hurt.

LG: He said...

JS: It might be that this total freedom doesn’t work for everybody.

AK: Maybe.

JS: But Len was fifteen when he left the school. He went to Rutgers, [laughs] he got all these degrees. It couldn’t have hurt him too much! [laughs] I laugh at him when he says this. I say, you got your PhD at MIT for Christ’s sakes! How can you say that the school...?

This transcription was kindly produced by Liz Lawler. It is published here slightly out of chronological order. A full version of the interview in chronological order can be found here.

If you enjoyed this article and feel called to give back to ASDE, here are ways you can support our work:

- Donate money

- Share our content with others! Click one of the buttons above to easily share on Twitter, Facebook, or email.

- Consider becoming a Contributor for Tipping Points

Tipping Points Magazine amplifies the diverse voices within the Self-Directed Education movement. The views expressed in our content belong solely to the author(s). The Alliance for Self-Directed Education disclaims responsibility for any interpretation or application of the information provided. Engage in dialogue by reaching out to the author(s) directly.